A history of neuroscience at Oxford

Our researchers have been unravelling the mysteries of the mind and developing treatments for mental health illnesses for centuries. The term neurology was even coined here.

So, what can we learn from the past? Do the theories and findings of luminaries from the 17th century still influence the neuroscientists and experts of today?

The story of Oxford’s involvement in brain and mental health stretches back hundreds of years – but let’s start with one pivotal year. A year that connects two key Oxford figures, whose influence is still felt today.

It’s 1621. Robert Burton has just published The Anatomy of Melancholy, and Thomas Willis has just been born.

Christ Church College, where both Burton and Willis studied

Christ Church College, where both Burton and Willis studied

Robert Burton (1577–1640)

Who was Robert Burton?

Born in Leicestershire in 1577, Robert Burton matriculated as a student at Brasenose in 1593 where his older brother William was already a student.

In 1599 he moved to Christ Church, where he was awarded his BA in 1602. He remained at Christ Church for the rest of his life, becoming a Bachelor of Divinity in 1614 and College Librarian in 1624.

While College Librarian, Burton drew on works from Christ Church’s ‘Old Library’, and the Bodleian Library when compiling his The Anatomy of Melancholy – a vast encyclopaedia on the subject of depression.

‘Known to few men, quite unknown to even fewer, here lies Democritus Junior, for whom melancholy provided life and death’

When Burton died in 1640, his personal library – a collection of at least 1,700 titles – was split between Christ Church and the Bodleian.

What is the Anatomy of Melancholy?

First published in 1621, Burton’s The Anatomy of Melancholy has long been hailed as both an extraordinary piece of English prose, and as a major early work of cognitive science.

An instant success, Anatomy represents an early modern understanding of the mental and physical phenomena that are currently being explored in research that connects the gut and mental health.

‘I write of melancholy, by being busy to avoid melancholy. There is no greater cause of melancholy than idleness, no better cure than busyness’

The emphasis that Burton placed on changing an individual’s environment, for example on diet, exercise and sleep, anticipates current interest in non-pharmaceutical remedies such as social prescribing and lifestyle changes.

After publication, Anatomy went through five editions in Burton’s lifetime alone – more than doubling in size.

Illustration of Robert Burton by Jim Godfrey, Verger, Christ Church (2019)

Illustration of Robert Burton by Jim Godfrey, Verger, Christ Church (2019)

Portrait of Robert Burton by Gilbert Jackson (1635)

Portrait of Robert Burton by Gilbert Jackson (1635)

Robert Burton's 'The Anatomy of Melancholy' (1621)

Robert Burton's 'The Anatomy of Melancholy' (1621)

Melancholy: A New Anatomy

To commemorate the 400th anniversary of the publication of The Anatomy of Melancholy, a diverse group of academics from the University’s Departments of Psychiatry, English and Clinical Neurosciences collaborated on a multidisciplinary exhibition that took place at the Bodleian’s Weston Library.

‘The nature of - and evidence-base for - modern therapies may have changed, but they often bear a remarkable resemblance to those first suggested by Robert Burton 400 years ago’

Curated by Oxford experts in mental health research and the humanities, the exhibition looked at how Burton’s concepts of holistic and multifaceted cures find surprising echoes in contemporary psychiatry and prescriptions for mental health.

A year before the exhibition, a BBC Radio 4 Series – The Anatomy of Melancholy – was aired, with twelve episodes looking at Burton’s work to find out how far we have come in the following four centuries.

Experts from across the University feature in the series, including Dr Kathryn Murphy, Professor David Clark, Professor John Geddes and Professor Colin Espie.

Dr Joseph Butler on the similarities and differences between contemporary medical care for those with severe mental health issues and Robert Burton's approach to medical care for "melancholy"

Professor John Geddes on the overlap between contemporary research on exercise and its impact on mental health and the approach to exercise and melancholy outlined by Robert Burton

Dr Philip Burnet on Robert Burton's ideas of diet and melancholy in the Anatomy of Melancholy (published 1621) and the advances in contemporary research on diet and mental health today.

Dr Kate Saunders, Professor in the Department of Psychiatry, on her interest in music, its impact on mental health, and its echoes as a cure for melancholy in Robert Burton's Anatomy of Melancholy

Dr Stephen Puntis on contemporary research into the impact of being in green space on our mental health, and the similarities and differences described by Robert Burton of being outside as a cure of melancholy

Dr Simon Kyle on contemporary research into the impact of sleep on mental health, and the advances made in understanding since Robert Burton connected sleep and mood in his Anatomy of Melancholy

Thomas Willis (1621-75)

Early years and the English Civil War

Thomas Willis was born in 1621 – the same year that Burton published The Anatomy of Melancholy.

He grew up a few miles outside of Oxford, where his family farmed as tenants of St John’s College. In 1638 Willis matriculated into Oxford as a student at Christ Church, receiving his BA in 1639. Willis obtained his MA in 1642, the very same month that the English Civil War broke out.

As part of the celebration of the quatercentenary of Thomas Willis’s birth, Professor Zoltán Molnár spoke to experts form a variety of disciplines about the influence of Willis’s work. St John’s College, which owned the land the Willis family farmed on during his younger years, also produced an online exhibition, highlighting his life and career.

Professor of the Global History of Medicine Erica Charters spoke to Professor Molnár about how the Civil War interrupted Willis’s medical training, but saw him surround himself with an exceptional group of colleagues.

Practicing medicine

As a reward for his loyalty to the royalists, Willis was awarded a Bachelor of Medicine degree by King Charles I in 1646. From this point onward, Willis was licensed to practice medicine.

Records show that Willis practiced medicine in Oxford, and surrounding towns and villages, with growing success and renown – increasingly so after having been involved in the resuscitation of Ann Greene after her attempted execution by hanging in December 1650.

After becoming arguably the wealthiest man in Oxford, in 1657 Willis purchased Beam Hall, opposite Merton College. He would reside here for the next decade.

Willis’s notes and correspondences with colleagues reveal a caring and dedicated clinician – one whose account of his patients has clear similarities to the way clinicians think today. His modern view on disease is one of his greatest legacies.

In conversation with Professor Kevin Talbot, Head of the Nuffield Department of Clinical Neurosciences, Professor Molnár explores Willis’s approach as a doctor, and the extent to which his descriptions of the diseases he encountered hold up today.

Discoveries, publications and legacy

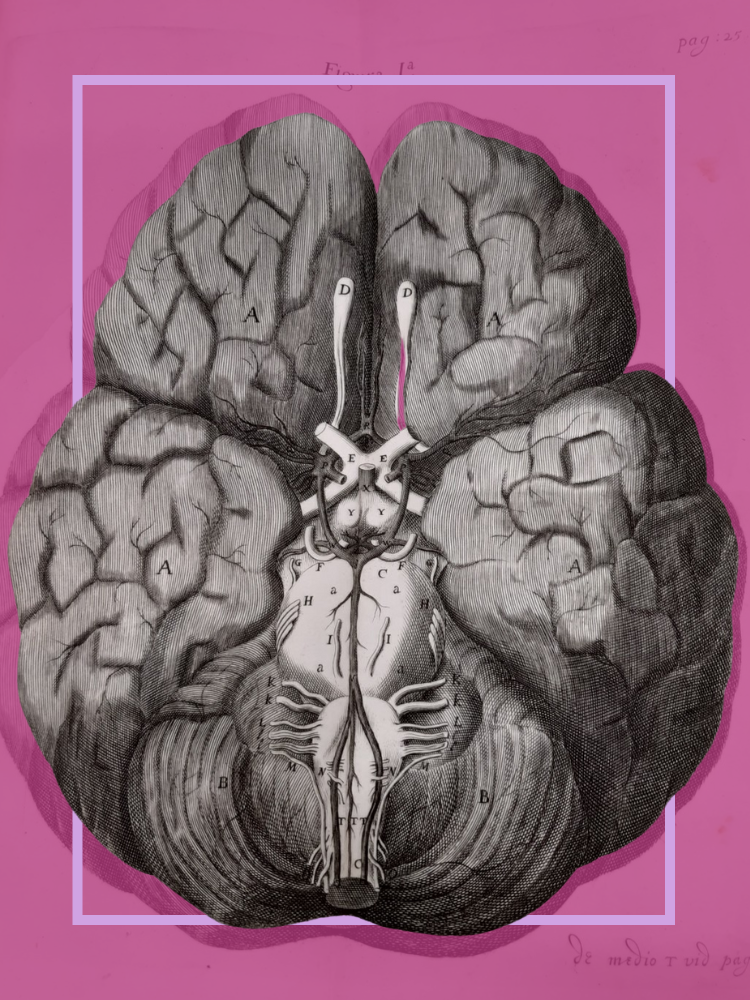

Willis transformed clinical medicine, and in 1660 began brain dissections, with his first observations published in Cerebri Anatome (1664).

During this period, Willis collaborated with, and was assisted by, a number of luminary figures. John Locke, one of his assistants in the 1650s, would later coin the term ‘cell’. Sir Christopher Wren, architect of St Paul’s Cathedral and the Sheldonian Theatre, provided Willis with illustrations for his work.

Another of Willis’s protégés was the medical doctor Richard Lower, who would go on to publish on circulation in the heart and perform the first blood transfusion.

Credited with the discovery of the arteriosus circle at the base of the brain – now named the ‘Circle of Willis’ – Willis made pioneering observations of various neural structures; his naming system, or nomenclature, is still in use today.

He conceptually dissociated voluntary movements that originate in the cortex, from involuntary ones that occur in the cerebellum, and was the first person to propose that the higher cognitive function of the human brain comes from the convolutions of the cerebral cortex.

Owing to his original observations and critical views, his way of observing and treating patients was different to that of most of his contemporaries, marking the transition between medieval and modern notions of brain function.

Portrait of Thomas Willis from an engraving by David Loggan in 1667

Portrait of Thomas Willis from an engraving by David Loggan in 1667

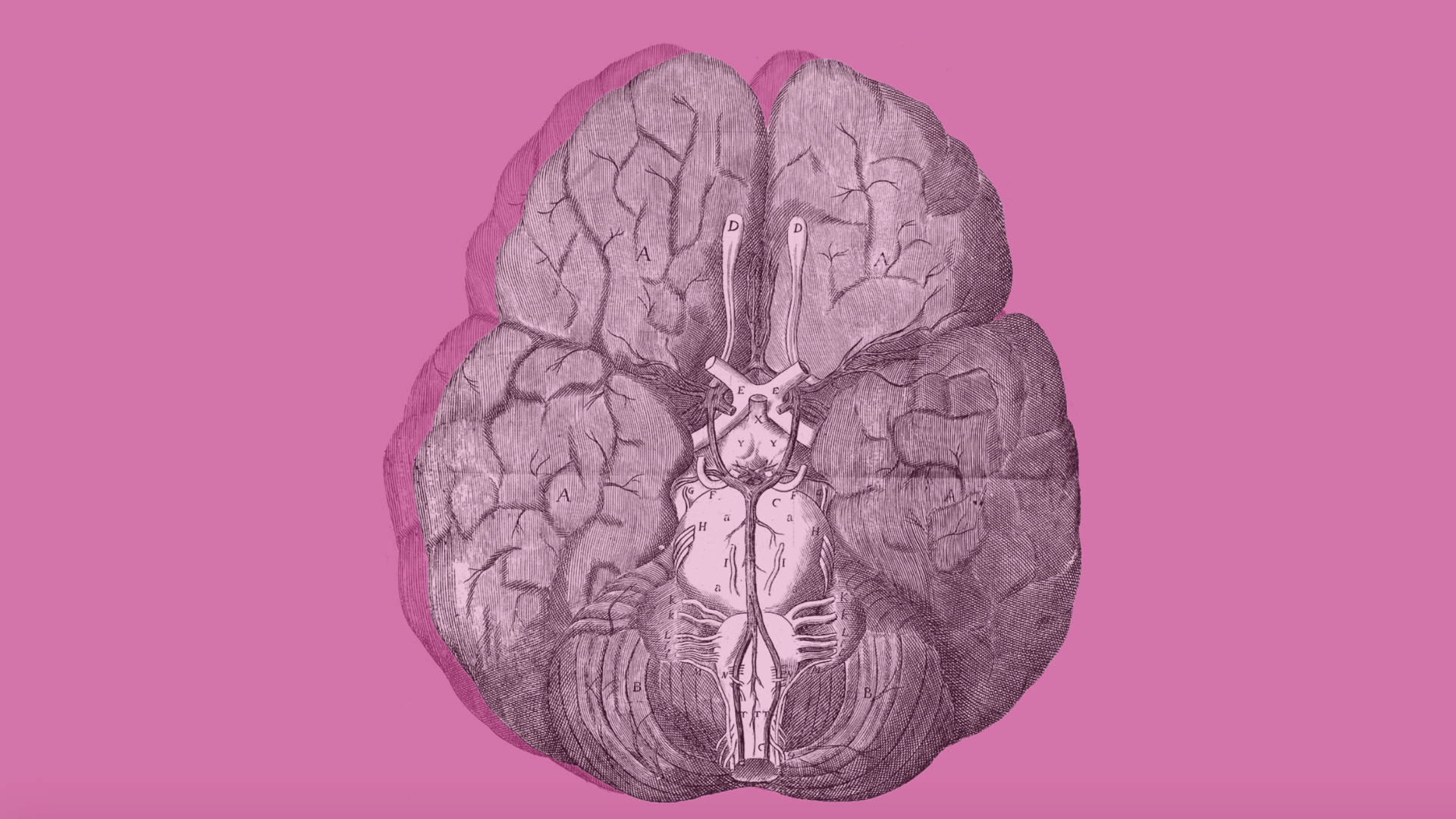

Christopher Wren's illustration of the so-called 'Circle of Willis' (1664)

Christopher Wren's illustration of the so-called 'Circle of Willis' (1664)

The history of our neuroscience departments

Wolfson Centre for the Prevention of Stroke and Dementia (CPSD) based at the new Wolfson Building

Wolfson Centre for the Prevention of Stroke and Dementia (CPSD) based at the new Wolfson Building

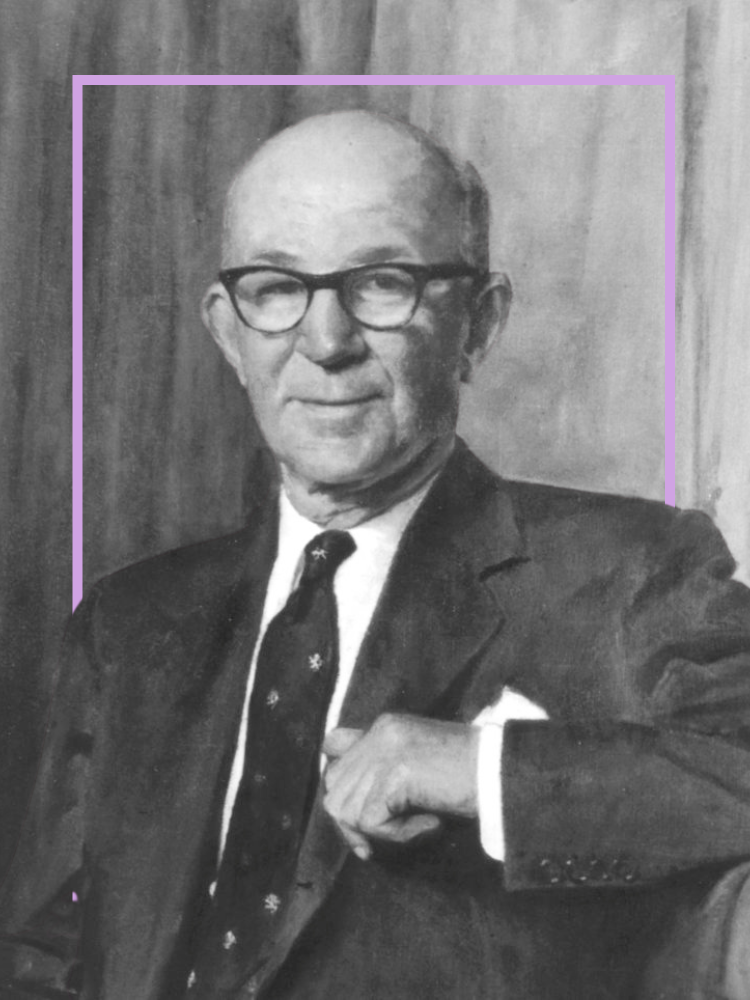

Professor Sir Robert Macintosh

Professor Sir Robert Macintosh

Department of Psychiatry, Warneford Hospital

Department of Psychiatry, Warneford Hospital

Oxford Neuroscience

The Oxford Neuroscience committee is responsible for the current and future strategy of neuroscience research at the University.

The committee represents a broad community of over 200 principal investigators and is made up of representatives from key neuroscience departments and areas, including:

- Clinical Neurosciences

- Psychiatry

- Experimental Psychology

- Physiology, Anatomy and Genetics

- Pharmacology

Clinical Neurosciences

The Nuffield Department of Clinical Neurosciences (NDCN) was formed in 2010 by bringing together the Department of Clinical Neurology, the Nuffield Laboratory of Ophthalmology, the Nuffield Division of Anaesthetics and the Oxford Centre for Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging of the Brain (FMRIB).

In 2015 the Centre for the Prevention of Stroke and Dementia was created, and in 2020 the MRC Brain Network Dynamics Unit moved into the department.

The oldest of these constituent areas is the Nuffield Department of Anaesthetics, established in the 1930s thanks to a conversation between Dr Robert Reynold Macintosh and Lord Nuffield, who later donated £2m (worth £130m today) to set up a Centre for Postgraduate Medicine with chairs of medicine, surgery, gynaecology and obstetrics, and finally, anaesthetics.

Dr Macintosh was made Nuffield Professor of Anaesthetics in 1937, making him head of the first independent department of anaesthesia in the UK, Europe and the Commonwealth – a post he held until 1965.

Eminent figures such as Professors Alexander Crampton Smith (1965-79), Sir Keith Sykes (1980-91), Pierre Foëx (1991-2002) and Clive Hahn (2002-06) followed until two Nuffield chairs were created in 2006.

Henry McQuay was made Professor of Clinical Anaesthetics, and Irene Tracey was made Professor of Anaesthetic Science.

Professor Tracey later became Director of the FMRIB and Head of the Nuffield Department of Clinical Neurosciences, before being admitted as Vice-Chancellor of the University in 2023.

The next constituent part of NDCN to be formed was the Nuffield Laboratory of Ophthalmology (NLO) in 1942, again established as a gift from Lord Nuffield.

Key figures in the history of the NLO include Dame Ida Mann, the first woman ever to hold the position of Professor at Oxford. Today, the Nuffield laboratory is headed by Russell Foster, Professor of Circadian Neuroscience.

The Division of Clinical Neurology (DCN) followed in 1966, established by Ritchie Russell, who became the first holder of the Chair of Clinical Neurology. The DCN has a broad portfolio of research that includes neurogenetics, neuroimmunology, neurodegenerative disorders, multiple sclerosis, neuromuscular and cerebrovascular diseases, and neuropathology.

In 2016 Professor Kevin Talbot took on the role of head of DCN, a post now held by Professor David Bennett, with Professor Michele Hu as deputy.

Originating from the Oxford Centre for Functional MRI of the Brain (FMRIB) that was founded in 1998, the Wellcome Centre for Integrative Neuroimaging consists of around 250 members, aiming to bridge the gap between laboratory neuroscience and human health. In 2015 Professor Heidi Johansen-Berg was appointed Director of FMRIB.

Psychiatry

The Department of Psychiatry celebrated its 50th birthday in 2019, having been founded in January 1969 by Professor Michael Gelder.

Now a department with over 250 staff, including more than 170 researchers, the department is based at the Warneford Hospital and led by Professor Belinda Lennox.

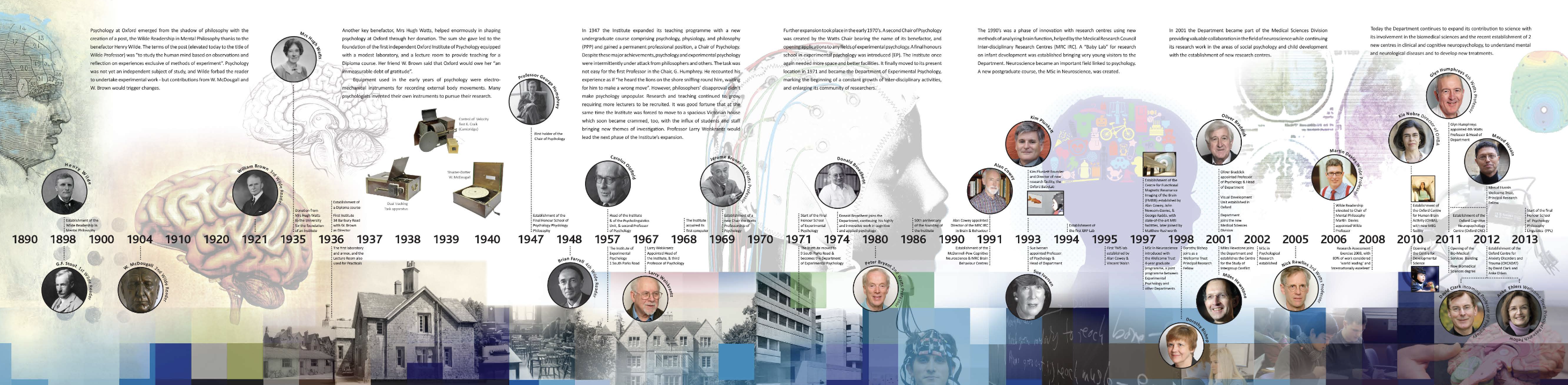

Experimental Psychology

1898 marked the beginning of the official study of psychology at Oxford with the founding of the Wilde Readership in Mental Philosophy.

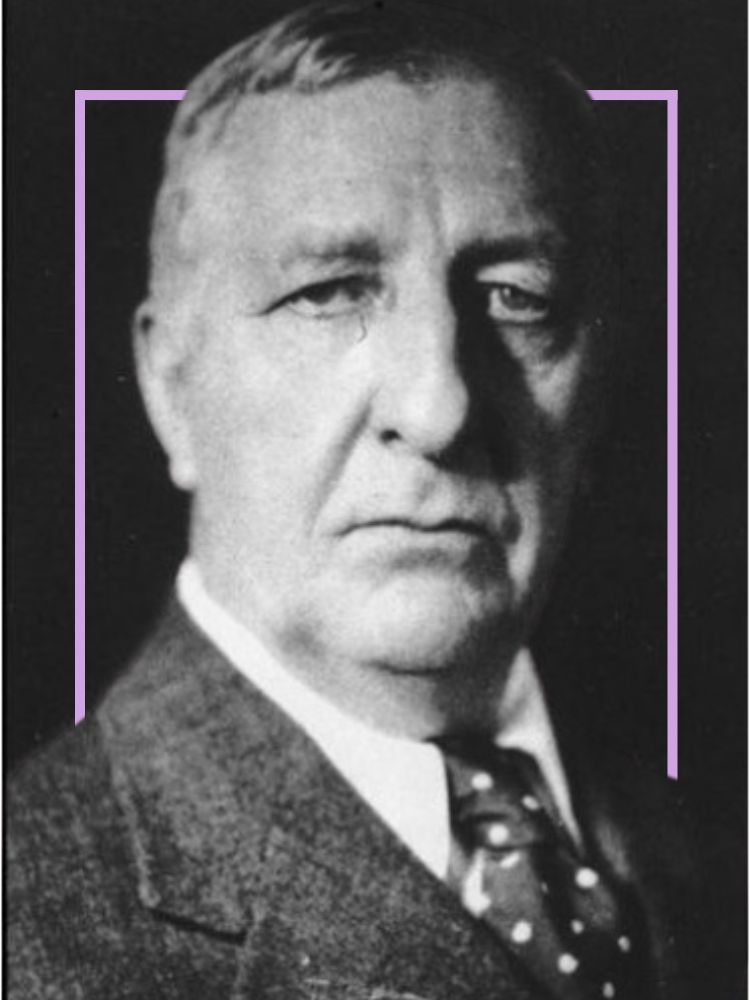

Between 1915 and 1919, the second holder of the post, Professor William McDougall, left Oxford to serve as a major in the Royal Army Medical Corps, where he specialised in treating soldiers with ‘shell shock’. In 1935, a donation from Mrs Hugh Watts enabled the foundation of an institute on Banbury Road.

Professor George Humphrey became the first holder of the Chair of Psychology as the Final Honour School of Psychology, Physiology and Philosophy was established in 1947.

By 1957 the new Institute of Experimental Psychology had outgrown its Banbury Road home and moved to South Parks instead, finally becoming the Department of Experimental Psychology in 1970.

Key figures in the history of Psychology, such as Donald Broadbent, Jerome Bruner, Anne Treisman, Larry Weiskrantz, Alan Cowey, Dorothy Bishop and Dick Passingham, have all taught at Oxford, and the department is currently being led by Professor of Cognitive Neuroscience Matthew Rushworth.

Physiology, Anatomy and Genetics

The teaching of medicine at Oxford goes back at least eight centuries, and although the Anatomy School was built in 1619, the Department of Physiology, Anatomy and Genetics wasn’t established in its current guise until 2006. The Centre for Neural Circuits and Behaviour, and the Centre for Integrative Neuroscience were opened as part of the department in 2011 and 2018 respectively.

Oxford figures in these fields have been hugely influential, with a particular ‘golden period’ occurring in the second half of the 17th century due to a distinguished group of experimental scientists that went on to found the Royal Society in 1660.

Thomas Willis was one of these scientists, and alongside his pupil Richard Lower, he demonstrated the physiological importance of blood circulation to the brain, as well as advanced research into the anatomy of the brain system. He has since been regarded as the father of clinical neuroscience.

In 1913 Sir Charles Scott Sherrington was appointed Waynflete Professor of Physiology, and in 1932 he received the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine.

Sherrington is noted as having transformed modern neurophysiology, and was doctoral advisor to John Eccles, the neurophysiologist who was also awarded a Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1963 for this work on the synapse.

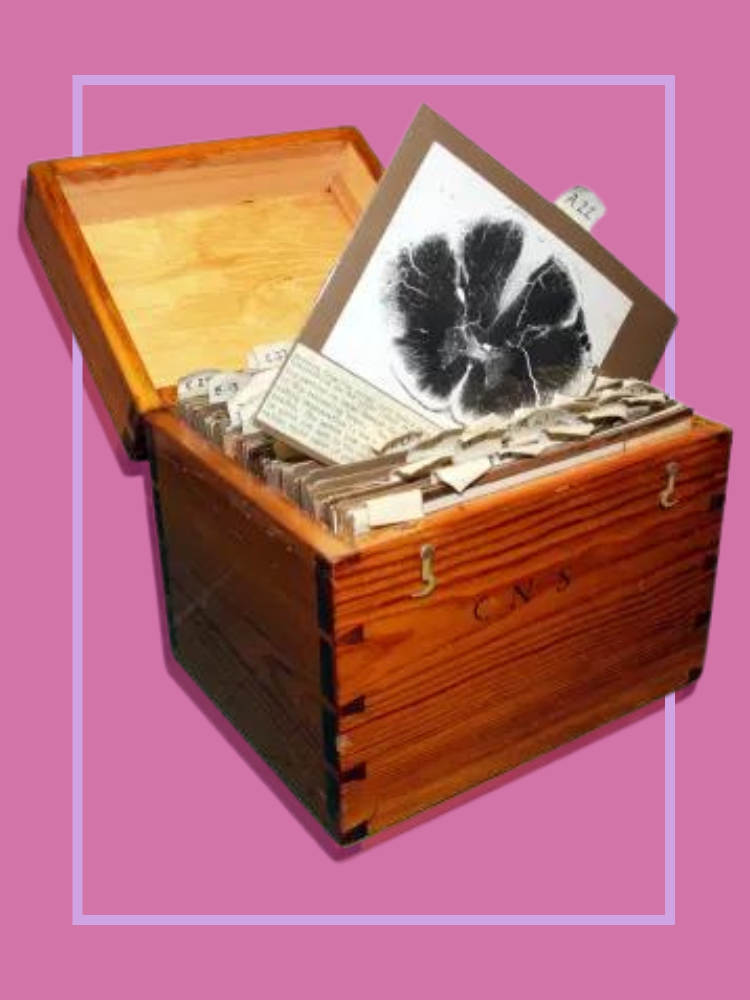

Professor Zoltán Molnár showcases Professor Sherrington's box of microscopic slides, explaining his significant influence on neuroscience

In 1934, WE Le Gros Clark accepted an invitation to a Professorship in Anatomy – he was particularly interested in the anatomy of the brain, especially in relation to colour vision.

Colin Blakemore was appointed Waynflete Professor of Physiology in 1979. At 35, Blakemore was the youngest person appointed to the position, and went on to contribute significantly to our understanding of vision, and how the brain develops and adapts.

The Department of Physiology, Anatomy and Genetics is currently led by Professor David Paterson, a post he has held since 2016.

Pharmacology

The Department of Pharmacology began life in 1912, from a single room in the University Museum.

Notable figures from the Department’s past century include Professor Sir William Paton, the creative mind behind the first effective treatment of blood pressure, and Sir John Vane, who was instrumental in the understanding of how aspirin produces pain relief and anti-inflammatory effects.

The department was also home to Professor Edith Bülbring, one of the first women to be accepted as a Fellow of the Royal Society. Professor Hermann (Hugh) Blaschko moved to the department in 1944, contributing information essential in the development of some invaluable drugs.

The department houses around 220 researchers, postgraduate students and support staff, and is currently led by Frances Platt, Professor of Biochemistry and Pharmacology.

Professor William McDougall (1871-1938)

Professor William McDougall (1871-1938)

W.E. Le Gros Clark's Slides Box

W.E. Le Gros Clark's Slides Box

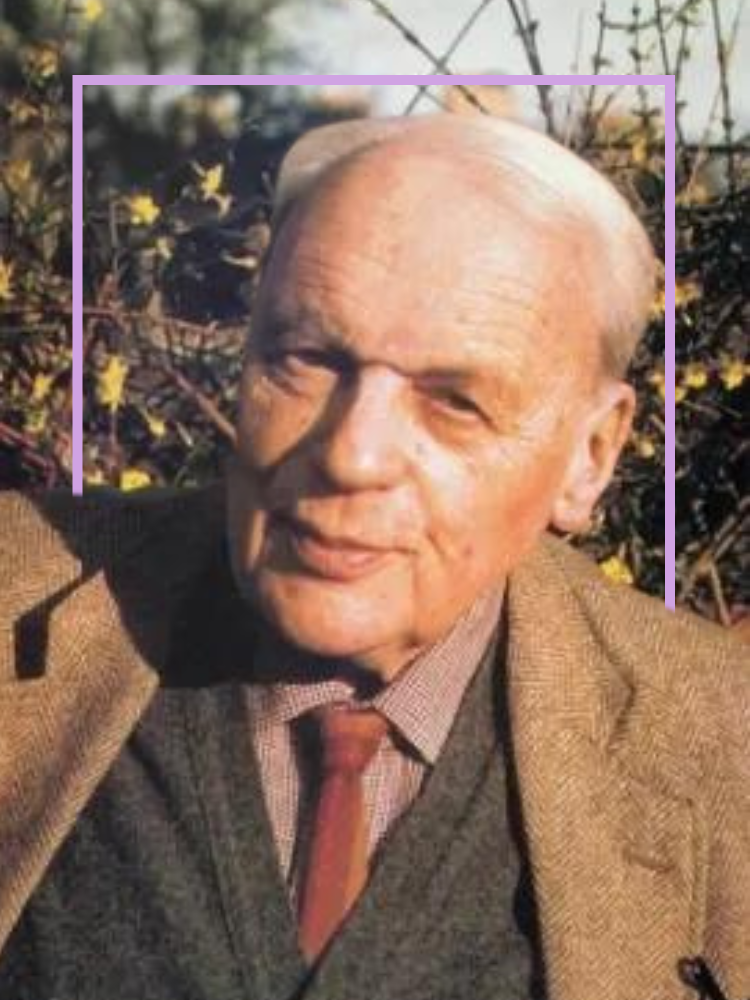

Professor Herman (Hugh) Blaschko (1900-1993)

Professor Herman (Hugh) Blaschko (1900-1993)

Looking to the future

After more than 400 years of research on brain and mental health, what does the future look like?

Experts from Oxford are striving to understand more about the brain and are developing new and innovative ways to treat mental health conditions.

Future-proofing mental health treatment

Working with researchers from a number of leading UK universities, Oxford academics are helping to shape the overarching goals that will speed up the implementation of mental health research and give a clear direction for researchers and funders to focus their efforts when it comes to better understanding the treatment of mental illness.

‘National high-level goals that focus our research efforts are an important part of ensuring that good will and good intentions are translated into genuine innovations and impact’

Following a consultation process organised by the Department of Health and Social Care convened by the Chief Medical Officer, the researchers set out four ambitious targets.

Firstly, to halve the number of children and young people experiencing persistent mental health problems. Secondly, to improve our understanding of the links between physical and mental health, and eliminate the mortality gap

Thirdly, to increase the number of new and improved treatments, interventions and supports for mental health problems. And finally, to improve the availability of choices and access to mental health care, treatment and support in hospital and community settings.

Using AI and VR to revolutionise care

The use of artificial intelligence and virtual reality to revolutionise mental health care is also high on the agenda for some of Oxford’s leading experts.

One such project, CHRONOS, was one of 38 projects to be supported by the second wave of the NHS AI Lab’s AI in Health and Care Award – the first time a mental health project had been a recipient.

‘CHRONOS will use AI technology to examine historical, anonymised medical notes to learn how care teams make decisions about treatment for individual patients’

The award means that the NIHR Oxford Health Biomedical Research Centre (BRC) will be able to make it easier for clinicians in secondary mental health care to rapidly identify the most appropriate treatments for their patients.

Researchers are also investigating the use of virtual reality to help transform psychological therapy. Daniel Freeman, Professor of Clinical Psychology, is the founder of OxfordVR.

A pioneering clinical trial developed by Professor Freeman’s team tested whether VR could be used as an intervention for people with a fear of heights.

A multi-partner team of university, health and industry experts, including OxfordVR and Professor Freeman, have also conducted the largest ever clinical trial of virtual reality for mental health in a bid to treat agoraphobia and anxiety.

The gameChange VR program led to significant reductions in the avoidance of everyday situations and in distress having been trialled with 346 patients with psychosis in nine NHS Trusts across five English regions – Bristol, Manchester, Newcastle, Nottingham and Oxford.