Behind the scenes at Oxfordshire's dinosaur highway.

Oxford may today be known for its ‘dreaming spires’ but it was once a land of tropical mires upon which colossal reptiles walked, leaving their marks to be found millions of years later.

Go behind the scenes with Dr Caroline Wood to uncover one of the most exciting dinosaur trackways in the world.

Oxford may today be known for its ‘dreaming spires’ but it was once a land of tropical mires upon which colossal reptiles walked, leaving their marks to be found millions of years later.

Go behind the scenes with Dr Caroline Wood to uncover one of the most exciting dinosaur trackways in the world.

The air pulses with seismic activity and under our feet deep vibrations race across the ground.

Every so often, a shattering rumble rips out across the surroundings.

Dr Emma Nicholls, a vertebrate palaeontologist at Oxford University Museum of Natural History (OUMNH), has to shout to make her voice heard ‘… they are huge and they can’t see you. Remember, do not leave the designated safety area under any circumstances!’

We all nod diligently, assuring her we have understood.

Looking down at the immense footprints a few metres away, I try to imagine how painful it would be to be squashed by the foot of a ten tonne sauropod dinosaur.

I’m pretty sure my hard hat wouldn’t be very effective protection… however, it isn’t dinosaurs that are rumbling and thundering all around us today, but thoroughly 21st-century quarry vehicles.

Author Dr Caroline Wood, at the dig site at Dewars Farm Quarry in North Oxfordshire

Author Dr Caroline Wood, at the dig site at Dewars Farm Quarry in North Oxfordshire

On a scorching hot summer’s day, I’ve come to help uncover a newly-discovered section of one of the longest dinosaur trackways in the world, here in North Oxfordshire.

Whilst stripping back clay from the ground with his vehicle, quarry worker Gary Johnson stumbled upon a series of exquisitely preserved dinosaur footprints.

The OUMNH team were called, and they soon made a visit to the site with two colleagues from the University of Birmingham.

What they found was something really special; tracks from not just one type of dinosaur but at least two: a herbivorous sauropod (thought to be Cetiosaurus) and the terrifyingly-armed carnivore Megalosaurus, both hailing from the Middle Jurassic, approximately 166 million years ago.

This week, Smiths Bletchington have given site access to a team of researchers, students and staff from the Universities of Oxford and Birmingham.

Our task today is to uncover the prints as much as possible, capture digital records, then create computer models to enable researchers across the world to study them further.

As someone who has been obsessed with dinosaurs practically from birth (my first toy was a Triceratops), it feels like all my Christmases have come at once.

‘It’s amazing how much information you can get from a single footprint’

It is not the first time that footprints from these dinosaurs have been found in the area.

In 1997, tracks from the same two types of dinosaur were unearthed at Ardley Quarry and Landfill Site in Oxfordshire, and can now be seen in the ‘Dinosaur garden’ at the Oxfordshire Museum in Woodstock.

But the newly-unearthed footprints, which link up with the original, make it by far the largest and most significant dinosaur track site in the UK.

‘Some people may feel they’re not as visually dramatic as fossilised skeletons, but dinosaur footprints are incredibly useful resources for palaeontologists,’ Emma says.

‘They can give us a wealth of information about how these animals moved and travelled. In addition, footprints and other trace fossils can also give direct evidence of the environment within which the organism existed.’

'It is possible that this huge Jurassic predator was tracking the sauropod to hunt.’

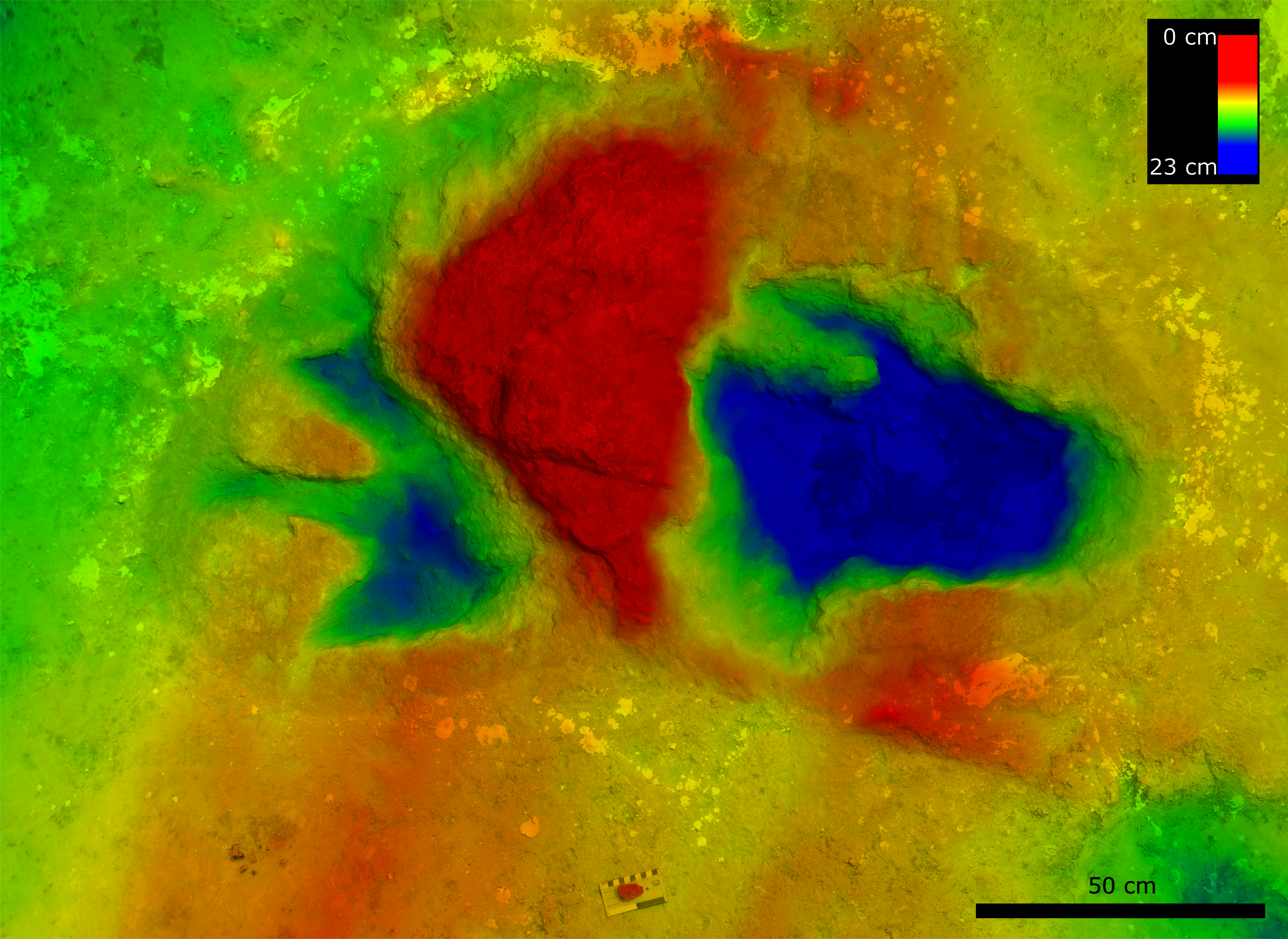

She points to the nearest Cetiosaurus tracks. ‘Each of the sauropod footprints has a distinct, raised ridge at the front’.

‘This indicates that the animal was walking in soft, wet sediment, but that it wasn’t so water-logged that the footprint collapsed. When the animal put its foot down, its weight caused the mud to splosh up in front, which has been preserved in situ.’

Dr Duncan Murdock, who is co-leading the excavation with Emma, as well as colleagues Professor Richard Butler and Professor Kirsty Edgar from the University of Birmingham, adds: ‘The climate here in the Middle Jurassic would have been warm and tropical, and the environment essentially a large, muddy lagoon.’

The sediment kicked up at the front of the prints was also the reason that the buried prints came to light in the first place, when quarry worker Gary Johnson felt the huge bumps as he worked to clear the mud with his vehicle.

Dinosaur footprints can also offer valuable clues into how different animals interacted, particularly when their tracks are found together, as they are here.

‘Here, we have trackways from at least four sauropods and one Megalosaurus,’ Duncan says. ‘Interestingly, the sauropods are a mixture of different sizes, so it is possibly a herd with juveniles or perhaps there are more than one type of sauropod represented here.’

At one point, the tracks intersect- which poses an interesting question for the research team – which dinosaur came first?

‘It looks as though the back of the Megalosaurus footprint has squished a section of the bump at the front of the Cetiosaurus print, meaning the carnivore came second,’ says Duncan. ‘Although inconclusive, it is possible that this huge Jurassic predator was tracking the sauropod to hunt.’

Artistic reconstruction of Megalosaurus and Cetiosaurus in the landscape of the Middle Jurassic, approximately 166 million years ago © Mark Witton 2024.

Artistic reconstruction of Megalosaurus and Cetiosaurus in the landscape of the Middle Jurassic, approximately 166 million years ago © Mark Witton 2024.

Getting my hands dirty.

With most of the prints only partially excavated, it’s time I made myself useful.

Fortunately, my lack of experience isn’t an issue; instead of high-tech specialist equipment, I am handed a bucket of supplies that could all be sourced from a hardware store.

I don gloves and set to work on a sauropod print with a brush, sweeping out dust and loose stones. Besides being a good workout, it is a highly multisensory experience as I look, feel and ‘hear’ my way around the giant print.

I am taught how to ‘listen’ for the edge of the print by tapping my shovel gently: the fossilised print gives a sharp, metallic ching whilst the surrounding mud makes a dull thump sound.

Slowly, under my hands, the full outline of the 90 cm long print is liberated. It amuses me to think how the enormous creature that stomped this way 166 million years ago would have been oblivious that, one day, a diminutive biped mammal would be sweeping out its footprints with assiduous, almost loving, attention.

I’m not the only one getting goose bumps. Emily Howard, a (second year going into third year) Earth Sciences undergraduate student at Oxford University is working on the footprint next to mine.

‘I feel really lucky to be doing this – there is no analogue for dinosaurs,’ she says. ‘When we have lessons in class, it often feels as though everything has already been found and documented… so to be involved with a new discovery and to play a part in the process of uncovering it is very special.’

Excavation equipment at the dig site. Image: Caroline Wood.

Excavation equipment at the dig site. Image: Caroline Wood.

‘To me, dinosaur trackways are much more “alive” than fossilised bones, which can only be from dead animals. Similar to when you see human footprints on a path ahead of you, a dinosaur track gives the impression that the creature could be miles away in the direction the tracks march on, but was here only a moment ago.’

Capturing all the details.

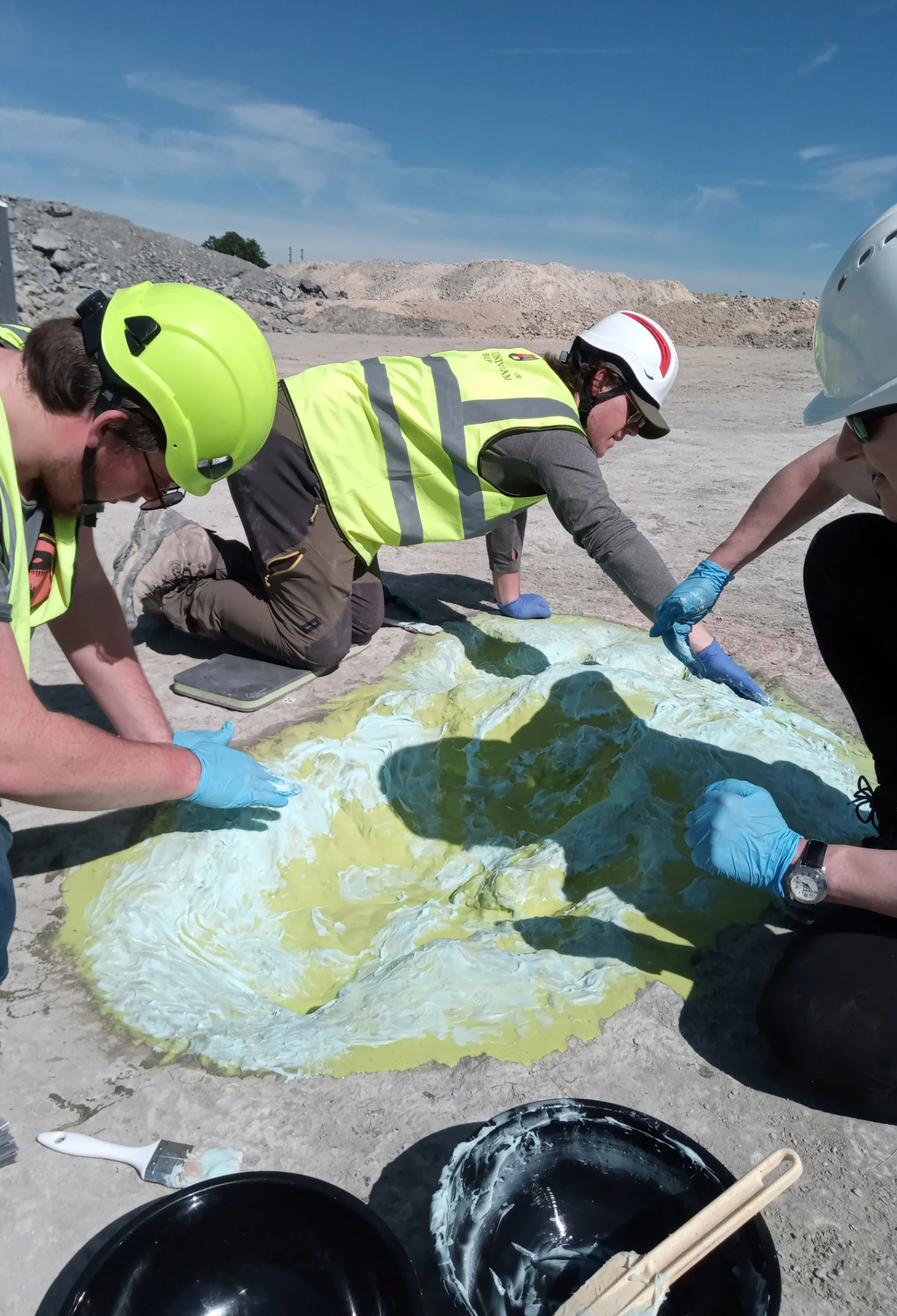

Nearby, one of the prints is undergoing more specialised treatment.

Juliet Hay, a conservator in palaeontology at OUMNH, is massaging what looks like viscous turquoise toothpaste into the centre of a print. In the intense midday heat (which helps the materials work more quickly than on a cold wet day), the various layers that make the cast will soon bind together and solidify to create a mould that can be peeled off like a beauty mask.

‘Using the mould, we will be able to make 3D casts of the prints from various different materials, both for research and public engagement.’

With so many prints to uncover, staff from all across OUMNH, as well as staff and students from the Universities of Oxford and Birmingham, have come to lend a hand, besides the collections team.

‘All the staff across the museum are excited,’ says Molly Appleby, Visitor Services Assistant at OUMNH.

‘The dinosaurs are such an iconic feature of our exhibits, so it is wonderful that we have all had the opportunity to be involved in this new discovery. This certainly makes a change to my day job!’

Creating a mould of one of the Megalosaurus footprints. Image: Caroline Wood.

Creating a mould of one of the Megalosaurus footprints. Image: Caroline Wood.

A volunteer takes photographs of one of the Megalosaurus prints. Image: Dr Caroline Wood.

A volunteer takes photographs of one of the Megalosaurus prints. Image: Dr Caroline Wood.

The team’s aim goes beyond making physical models. A key outcome is to digitally record the prints so that computer software can reconstruct 3D virtual models, that can be used by researchers across the world.

‘Using photogrammetry and computer models, we will be able to work out details such as the height of the animals and their speed,’ Duncan says.

‘On the largest sauropod’s track, one of the prints is slightly out of sequence – almost as though the animal stopped and looked back over its shoulder. Hopefully, the computer models will help solve that mystery.’

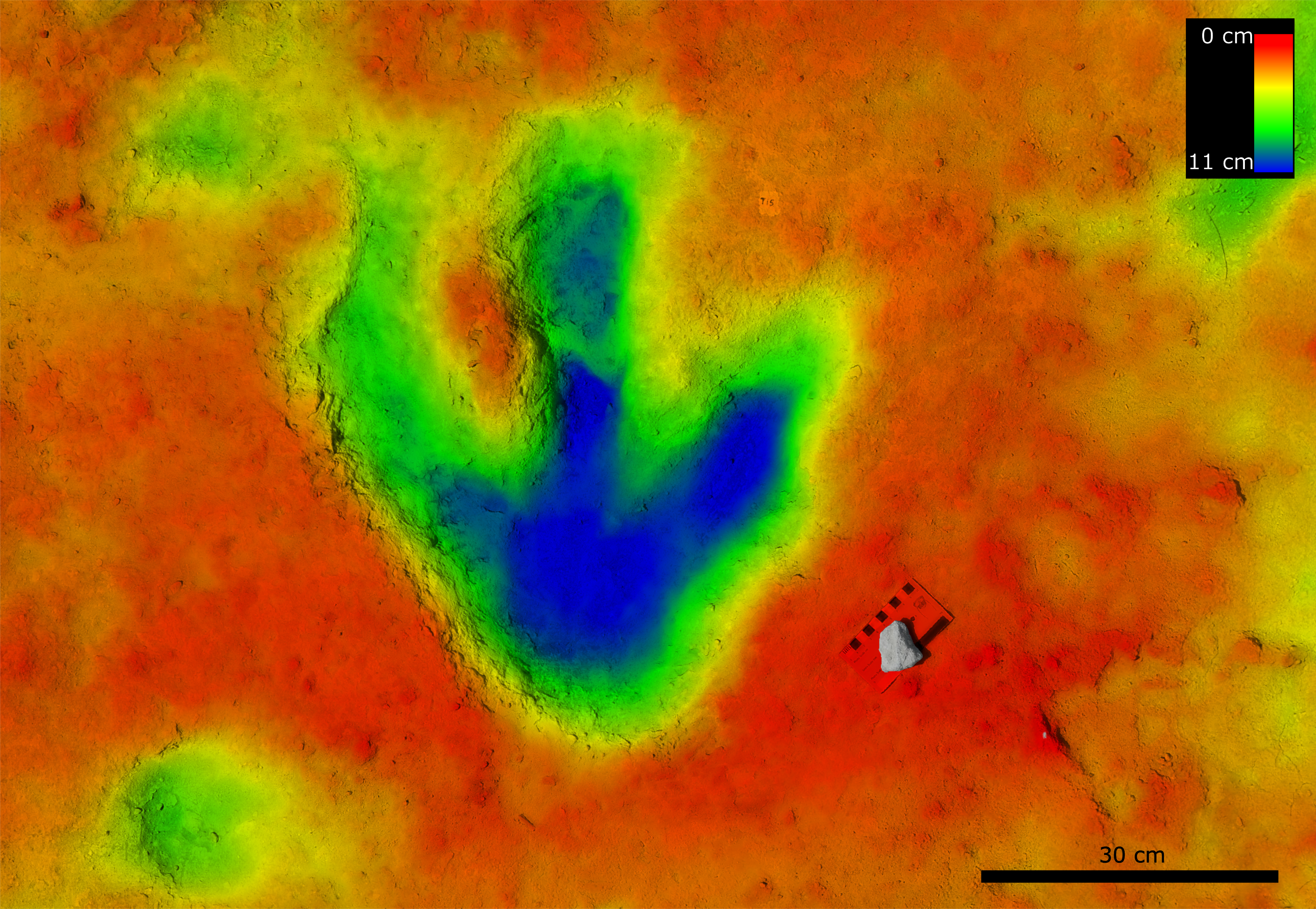

One of the Megalosaurus footprints coloured by depth. Credit: Dr Luke Meade, University of Birmingham.

One of the Megalosaurus footprints coloured by depth. Credit: Dr Luke Meade, University of Birmingham.

To do this, you need data – and lots of it. I join some of the students who are busy taking close-up photographs of each footprint from as many different angles as possible. Once again, the equipment is straightforward: a standard DSLR camera. In theory, one student tells me, you could even use a mobile phone.

The photographs will be fed into computer software that will identify points of similarity and use trigonometry to reconstruct a 3D model of the print. For each print, between 60 and 100 photos will be taken.

I’m told that more photographs are needed for the sauropod prints: being simpler shapes, it’s more taxing for the model to identify reference points.

‘This never ceases to be exciting’

‘Team- breaktime!’ As the sun reaches its noonday zenith, we convene under the OUMNH gazebos to escape into the shade.

We refuel and reapply sunscreen, swapping stories of childhood dinosaur addictions and favourite scenes from Jurassic Park. For Emma though, the real-life science of dinosaurs will always trump fictional parodies.

‘Duncan and I have been working with Mark Stanway and the Smiths Bletchington team at the Quarry for nearly two years now, and it never ceases to be exciting,’ she says.

‘Excavating a brand-new Megalosaurus trackway in the 200th anniversary year of the discovery of Megalosaurus – the first dinosaur to be scientifically named and described anywhere in the world – is very special indeed.’

As my eyes are drawn along the length of the largest sauropod trackway, over 150 metres long in total, I realise that the huge footprints disappear under the cliff at the edge of the quarry.

There are undoubtedly more tracks to be discovered…who knows what will be found in the future?

The area is still a working quarry with no public access, and will remain so in the medium term.

However, Emma, Duncan, Richard and Kirsty are actively working with Smiths Bletchington and Natural England on options for preserving the site for the future.

Curious to learn more?

You can get up close to a cast of one of the footprints and see other materials from the dig site at OUMNH’s Breaking Ground exhibition, which runs until 29 September 2025.

More from PULSE.