Language, literature and mental health

Experts at Oxford are examining how the written word can impact, and reflect the state of, our mental health.

Our researchers are working on new interventions for common speech disorders, and helping children overcome language development difficulties. They are discovering how our brains process language, and why it matters for our overall brain health.

Mental health depictions in literature

Eating disorders in literature

Self-help books are now commonly prescribed for many mental health conditions including eating disorders, and other books including fiction, poetry, and memoirs are often recommended by therapists or sought out by sufferers.

Little is known however about whether any kind of book can be therapeutically effective in managing or treating eating disorders.

To investigate this, Dr Emily Troscianko, a Research Associate in the Faculty of Medieval and Modern Languages, partnered with the eating disorders charity Beat to create an online survey which asked respondents about their experiences with literature and eating disorders.

Receiving nearly 900 responses, the survey provided an extensive dataset that illuminated important differences between literature whose characters explicitly experience eating disorders and other types of fiction that respondents reported enjoying.

Some respondents reported negative effects on their mood, self-esteem, feelings about their bodies, and diet and exercise habits.

For the respondents’ preferred type of other fiction, however, generally neutral or positive impacts were reported, which may shape conceptions of body image and individual identity in more complex and indirect ways.

One of the most sobering finds reported by survey respondents was the practice of ‘self-triggering’, where individuals deliberately sought out particular books (often fiction or memoirs about eating disorders) knowing that they were likely to make their disorder worse.

According to Dr Troscianko, the urgent need to understand what motivates this behaviour, its effects, and whether it can be undercut, makes a clear case for further, systematic research into creative bibliotherapy.

‘The partnership with Beat has yielded rich data from a large-scale survey which asked whether people perceive connections between their reading and their mental health, and if so, of what kind. The response was incredible; so many people have been in touch, telling us how important this topic is.’

Dr Troscianko presented the Textual Therapies podcast series, aiming to crystallise, communicate, and expand our understanding of how texts and health interact.

The episode What Does Disney do to Mental Health? explores the dangers of Disney’s take on poverty, mental health, and relationships.

The episode Computational Literary Studies and Mental Health looks at a project combining English literature, experimental psychology, and computational linguistics, with a focus on entropy, abstraction, and mental health.

Mental health and the written word

It is often said that we suffer as never before from the stress of information overload.

However, thanks to rapid industrialisation the Victorians diagnosed similar problems, with people forced to process more information in a month, it was claimed, than their grandparents had in a lifetime.

Diseases of Modern Life, an ERC-funded research project which ran from 2014-2019, explored the medical, literary and cultural responses in the Victorian age to the perceived problems of stress and overwork, and how these could offer new ways to contextualise similar issues today.

The principal investigator for the project, Professor Sally Shuttleworth from the Faculty of English, specialises in research that focuses on the inter-relations of literature, science and medicine.

This enabled the project to adopt an interdisciplinary approach to examine the holistic, integrative vision of the Victorians, as expressed in the science and in the great novels of the period, exploring the connections drawn between physiological, psychological and social health, or disease.

Through seminars, conferences, and innovative public engagement events, the project also harnessed the perspectives of the general public, psychologists, psychiatrists, GPs, service users, and historians of literature.

The Oxford Research Centre in the Humanities (TORCH) and researchers from the Diseases of Modern Life project teamed up with the award winning Projection Studio for Victorian Light Night, a spectacular large scale building projection and sound show onto Oxford's original Radcliffe Infirmary.

A key finding from the project was that the Victorians were acutely aware of the relationship between the new social conditions, technologies and work practices, and the problems these generated for health.

The project’s historically informed and multi-disciplinary approach also gave rise to Mind Reading, a series of conferences based on a simple question: do clinicians and patients speak the same language, and how might we use literature to bridge the gaps?

In particular, these explored how literature might function as a source of comfort or a frame of reference in moments of pain, trauma, and physical and mental illness.

The conferences also looked at how medical and clinical knowledge might be deployed and refracted through literary worlds; and whether literary techniques like textual analysis could help foster understanding between medical learners, healthcare providers, service users, and family members.

Children's language development

Early interventions

The Reading and Language group, part of the Department of Experimental Psychology, is led by Professor Maggie Snowling. The group aims to understand the causes of children’s learning difficulties and to develop effective interventions for these.

One of the group’s primary focuses is dyslexia and how this is linked to problems with spoken language development.

Dyslexia:

A learning difficulty that primarily affects the skills involved in accurate and fluent word reading and spelling. Characteristic features of dyslexia are difficulties in phonological awareness, verbal memory and verbal processing speed.

Key contributions in this area include the Wellcome Language and Reading Project, a six-year study which Professor Snowling led with colleagues from University College London and the University of York.

From 2007, the research team traced the development of 260 children from 3 to 9 years of age, using tests that assessed language, literacy and phonological skills. One of the major questions under investigation was whether early problems with speech and language affect a child’s ability to learn to read.

Among the key findings was that having a familial risk of dyslexia and poor language ability at preschool age were both significant risk factors for developing problems with reading.

Having a familial risk of dyslexia more than doubled the risk of early reading problems, and when this was accompanied by delayed language development, the risk was four times greater than for children generally.

Professor Maggie Snowling explains the causes of reading difficulties in Specific Language Impairment (now known as Developmental Language Disorder) and how they link to dyslexia and spoken language problems

The project also found that environmental factors had a large influence on reading ability. Socioeconomic status, home literacy environment, and early child health all independently predicted early literacy ability.

Further analysis revealed that the effects of socioeconomic status were partly mediated by the practice of parents reading storybooks to their children.

‘Together the findings underline the importance of the early years for fostering oral language and pre-reading skills for children at family-risk of dyslexia, and also more generally children who are socially disadvantaged.’

Building on this work, Professor Snowling and Professor Hulme developed the Nuffield Early Language Intervention: a low-cost and effective school-based intervention to help prevent at-risk children from later developing language difficulties.

The programme is designed to help children with relatively poor spoken language skills as they begin primary school, and is delivered over 30 weeks to groups of two to four children.

Professor Margaret Snowling, Professor Charles Hulme and local practitioners discuss the benefits of the Nuffield Early Language Intervention programme.

The programme was tested in randomised controlled trial which took place in 2018-2019 and involved over 1,150 pupils across almost 200 English schools.

The results found that the programme increased the language skills of 4- to 5- year-olds by an additional three months. Following this success, the project was developed into the NELI programme, a licensed intervention programme available to all schools.

Diagnosing and treating language disorders

Much remains unknown about why certain children develop language difficulties, particularly when there is no obvious cause, such as hearing loss or Down’s syndrome.

This is the focus of Professor Dorothy Bishop, from the Department of Experimental Psychology, whose recent work has particularly concentrated on Specific Language Impairment (now known as Developmental Language Disorder).

The condition, affecting around 3% of the population, causes otherwise healthy children to have extreme difficulty with talking and understanding language.

Developmental Language Disorder (DLD):

Developmental Language Disorder, or DLD, is when a child has long term difficulties in being able to use and understand language. If they speak more than one language, it will have an effect on all of these. This condition was previously known as Specific Language Impairment (SLI).

Professor Bishop’s research has shown that there is a strong genetic component to these disorders, and her current work is investigating whether the genetic variants that increase the risk of DLD are also implicated in other conditions, such as autistic spectrum disorder and developmental dyslexia.

In another line of research, Professor Bishop has also used measurements of brain activity to study how children with DLD respond to different sounds. This has found evidence that children with DLD engage larger and less focal brain regions than other children of the same age, especially when listening to speech sounds.

In an Oxford Impact film, Professor Dorothy Bishop talks about how academic and professional communities have worked together to decide on better ways of diagnosing and referring to children with language disorders.

Professor Bishop has also applied her knowledge of language and speech impairments to help develop a practical e-Learning course to support primary care practitioners.

Speech and Language Impairment in Children, published in 2016, teaches how to recognise when a child has a significant speech and language impairment, to understand when to refer, and to be aware of the impact this can have on the child's development and on the family.

Professor Bishop hosted the podcast series Children's Language and Literacy Impairments, focusing on why some children have DLD.

Confusion over terminology for language difficulties has existed for many years, hindering awareness and communication.

Professor Dorothy Bishop and Professor Maggie Snowling led a consensus process to decide on better ways of diagnosing and referring to children with language disorders.

In this RADLD film Professor Bishop explains the consensus process, how they came to agree on the term Developmental Language Disorder (DLD) and explains the criteria that they recommend for identifying DLD.

Supporting language development

How do children first begin to recognise words? Why are some words hard to read and understand? How do we comprehend what we read?

These are some of the questions Professor Kate Nation investigates with her research group ReadOxford, based in the Department of Experimental Psychology.

ReadOxford draws on a range of methods, including studies that measure children’s language and reading, and track development over time; laboratory experiments with adults that mimic natural language development; large-scale analyses of language data that reveal patterns of language in children’s books and in their own writing, and eye-tracking studies that measure cognitive processing in real-time, as children read.

‘Two sets of things are critical for early readers.... they have to understand how the writing system works – the idea that in a language like English, letters represent language via sound. It can be a penny dropping moment for some kids, as they begin to understand how the alphabet works.’

Professor Nation’s recent focus has been with ‘book language’. Relative to the language used in everyday conversations, written language is rich and sophisticated: it contains more words, and more words that are complex, emotional, and abstract. It is also more complex in terms of grammar.

Work by the ReadOxford group has found that these differences start early – the story books that toddlers listen to in the context of shared reading contain rich and complex language. Children who miss out on shared reading therefore miss out on this key language input, meaning that they may start school from a position of disadvantage.

Professor Nation’s current work is seeking to understand the implications of this for children’s language, literacy, and emotional development and from this, to develop ways to support children’s learning.

‘Two sets of things are critical for early readers.... they have to understand how the writing system works – the idea that in a language like English, letters represent language via sound. It can be a penny dropping moment for some kids, as they begin to understand how the alphabet works.’

Language processing and the brain

How the brain processes language

Although brain imaging technology is becoming increasingly sophisticated, there are still many unanswered questions surrounding many areas of language processing.

Answering these questions is the focus of The Language and Brain Laboratory, part of the Faculty of Linguistics, Philology and Phonetics and led by Professor Aditi Lahiri.

Professor Lahiri’s research programme employs a diverse range of methodologies, from cutting-edge brain imaging technology to palaeographic investigation of centuries-old manuscripts, with the overarching theme of investigating the mental representation and historical development of the sounds of human language.

The Language and Brain Lab’s recent projects include WORDS: Asymmetry, change and processing in phonological mental representation. Running from 2011-2016, this project combined approaches from historical linguistics, psycholinguistics, neurolinguistics, phonology, and computational modelling to examine the abstract representation of words.

A key hypothesis under test was that the abstract representation of words in the adult brain is also reflected in the development of words as indicated by historical data from manuscripts.

In April 2022, Professor Lahiri was awarded a major £2.9 million European Research Council Advanced Grant to examine the principle of pertinacity, or persistence. Whilst it is clear that natural languages change in time, this project takes the challenging view that phonology is pertinacious and changes in existing phonological systems are strictly limited.

A key question the Pertinacity Project will investigate is whether a particular phonological pattern persists but is extended to apply to new language forms and different outputs emerge, or whether language outputs look alike but the underlying phonological system alters due to changes elsewhere in the grammar.

‘The Pertinacity project will allow us to set out our expectations, and better understand the reasons behind the whys and why nots of phonological change. Classical historical research will be combined with psycho- and neurolinguistic experimentation and computational speech recognition to explore the central issues of linguistic change and stability, diversity and uniformity.’

Alongside this work, Professor Lahiri is working with colleagues from the University of Konstanz on the Complexity in Derivational Morphology project.

Running from 2020 to 2024, this is investigating the processing of complex derived words in English and German, focusing in particular on the neural structures underlying morphological processing using electroencephalogram (EEG) and functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI).

This will generate key insights into how the brain processes complex words, revealing, for instance, whether prefixes differ from suffixes both temporally and spatially in the brain.

Speech and language disorders

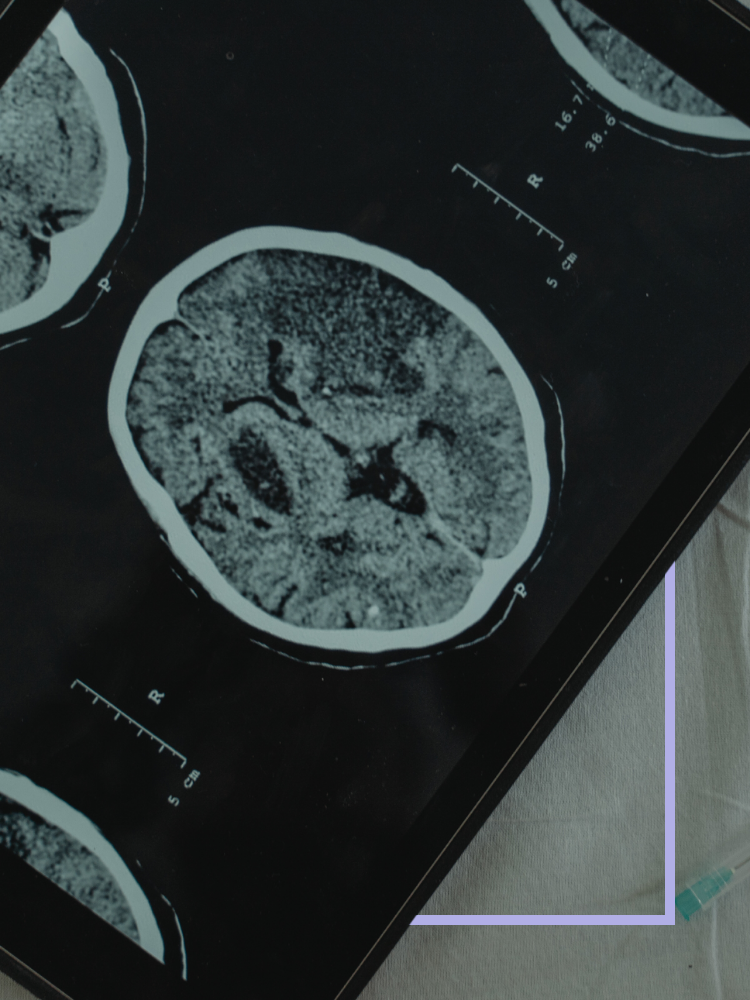

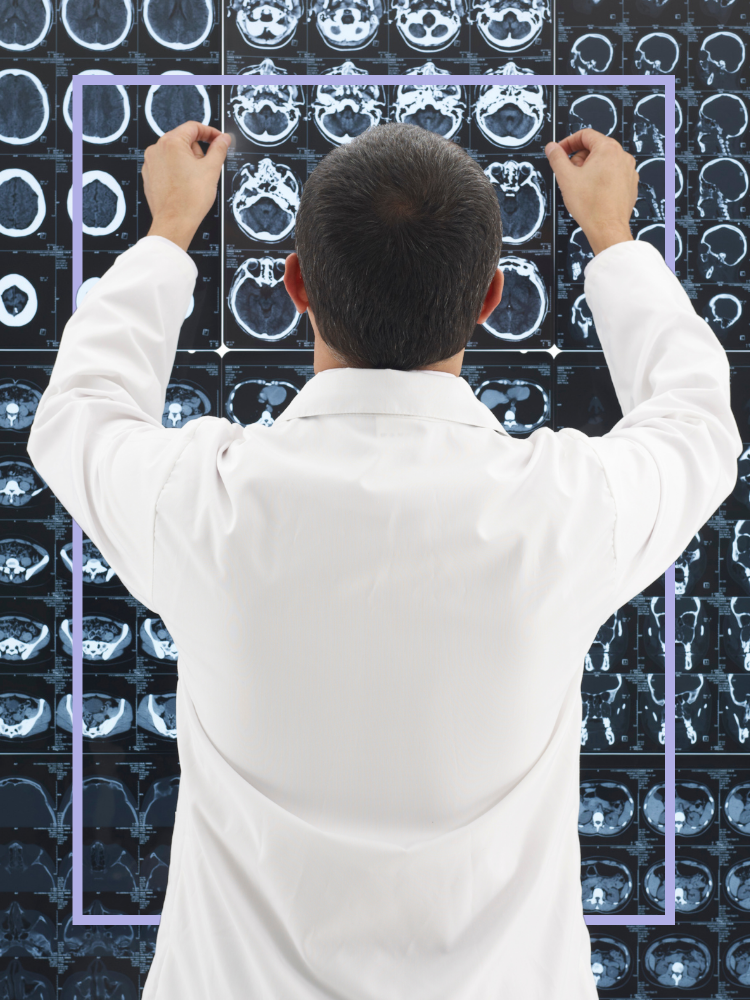

Brain scanning

Developmental Language Disorder (DLD) is characterized by difficulties in acquiring one’s native language for no apparent reason. This considerably increases the risk of having difficulties when learning to read, underachieving academically, being unemployed, and facing social and mental health challenges.

While DLD is a common developmental disorder, affecting approximately two children in every classroom, its neural basis is poorly understood.

The Speech & Brain Group, part of the Department of Experimental Psychology, and led by Professor Kate Watkins, are further investigating DLD and its underlying causes.

The group are leading the Oxford Brain Organisation in Language Development study (OxBOLD), using MRI scanning to image the brains of children with a range of language learning abilities including those with DLD.

As part of the OxBOLD study, the researchers used MRI brain scans that were specifically sensitive to different properties of the brain tissue, including the amount of myelin in the brain. Myelin is a fatty substance that wraps around neurons and speeds up transmission of signals between brain areas.

The results demonstrated that children with DLD have less myelin in parts of the brain responsible for acquiring rules and habits, as well as those responsible for language production and comprehension.

Further studies are now needed to determine if these brain differences cause language problems and how or if experiencing language difficulties could cause these changes in the brain.

‘This type of scan tells us more about the make up or composition of the brain tissue in different areas. The findings might help us understand the pathways involved at a biological level and ultimately allow us to explain why children with DLD have problems with language learning.’

Stuttering

Another research focus for the Speech & Brain Group is stuttering (also known as stammering), a disorder affecting approximately 1% of the adult population.

Stuttering/stammering:

A form of communication impairment, characterised by disruptions and stoppages in the fluency and timing of speech. It often starts in early childhood (usually from three and a half years onwards).

Using diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) and fMRI, the group have investigated whether there are differences in brain structure and function in people who stutter.

This found that, whilst reading sentences aloud, several brain areas were underactive or overactive in people who stutter compared to controls who do not stutter. Furthermore, for one of the underactive brain areas - the ventral premotor cortex – the data revealed that the integrity of the white matter was reduced in people who stutter.

In a MRI study, the group found a higher concentration of iron in the brains of people who stutter in the parts of the brain involved in movement initiation and control. These new findings might relate to some of the genetic findings that are thought to cause stuttering in about 10% of people who stutter.

It is not yet clear, however, if stuttering causes the increased iron in the brain or whether stuttering is caused by increased iron.

Professor Watkins discusses her research into stuttering, which makes use of MRI scans.

Besides investigating the fundamental mechanisms that may cause stuttering, researchers from the Speech & Brain group, including Dr Jennifer Chesters, are exploring potential interventions for stuttering.

The Investigating Noninvasive Stimulation to Enhance Fluency in People Who Stutter (INSTEP) trial is a randomised controlled trial investigating whether transcranial direct current stimulation can improve speech fluency in those who stutter.

The treatment, applied over five consecutive days, applied a very weak electrical current over the participant’s scalp for 20 minutes while they used fluency enhancers (choral reading and metronome-timed speech).

The results showed that the treatment reduced speech disfluency up to six weeks later, whilst participants who had the fluency enhancers but only "sham" stimulation showed no change in their fluency.

Dr Jennifer Chesters interviewed for StutterTalk about the results of the research.

The study team also applied vocal tract MRI for the first time to look at the speech movements of people who stutter. This revealed that people who stutter made more variable movements during fluent speech compared with people who are typically fluent.

A further study within the trial drew on previous research which indicated that people who stutter have an overactive response suppression mechanism.

The research team carried out fMRI of participants who were asked to respond to ‘stop’ and ‘go’ signals while performing manual tasks.

The results showed that people who stutter were slower to respond to ‘go’ stimuli than people who are typically fluent, but there was no difference in stop-signal reaction time. Furthermore, the fMRI data revealed that people who stutter showed significant overactivity of the inhibition network even during ‘go’ trials.

Combined, these results support a ‘global suppression hypothesis’, which proposes that people who stutter have an increased tendency to broadly and non-specifically inhibit motor responses.

Neural prosthetics

Remarkable progress has been made in recent years to develop technology that uses the brain’s encoding and muscle control commands to enable people who have lost the power of speech to be able to communicate. Such technologies can, however, be extremely invasive for the patient, requiring surgical procedures and risky brain implants.

Dr Oiwi Parker Jones, a Postdoctoral Researcher at the Oxford Robotics Institute, part of the Department of Engineering Science, is researching how to develop safe, non-invasive technologies for neural speech decoding.

These have the potential to help people suffering speech paralysis sooner, and without the need for surgical intervention. Patients those who have undergone a laryngectomy, suffered a traumatic brain injury, or had a stroke could benefit from such neural prosthetics, as could people with degenerative conditions such as Motor Neurone Disease.

‘Our goal is to create new communication tools for paralysed patients, such as those with locked-in syndrome, by developing non-invasive prosthetics that enable their inner speech to be heard – to give them the opportunity to communicate again without the danger of brain surgery.’

In January 2023, Dr Parker Jones was awarded a Medical Research Council Career Development Fellowship to create a new research group within the University’s Department of Engineering Science. This will comprise a multidisciplinary research team, including engineers, computer scientists, neuroscientists and clinicians.

Dr Parker Jones intends to use advanced brain imaging technology to apply the power of machine learning to large amount of high-quality neural data.

This will include developing new deep learning methods to decode inner speech from brain signals, with the ultimate aim being to create neural prosthetics that will restore patients’ ability to communicate with their caregivers and families.