Investigating the impact of sleep on brain and mental health

Professor Russell Foster is the perfect interviewee: thoughtful, self-deprecating, anticipating questions and delivering entertaining stories and reflections alike in whole sentences with a modulating tone and considerable energy.

He is a scientist who makes complex science sound accessible – and that is quite deliberate.

But he is no social media scientist. Despite his warmth and good humour, Professor Foster is an internationally-recognised academic, responsible for ground-breaking work in his specialism of Circadian Neuroscience and Sleep.

And he is busy; on the day of the interview, he heard he has been invited to be the Specialist Adviser for a House of Lords Science and Technology Select Committee.

But he is on a mission to demystify science. And with this irresistible combination of expertise and accessibility, he was interviewed in 2019 on Desert Island Discs, displaying his arch whimsy with several sleep-related discs, alongside his clear preference for serious opera.

And, in 2022, Professor Foster wrote a highly-rated popular science book, Life Time. It has won rave reviews from a litany of well-known people who might not usually be associated with science or academia.

Among fans of the work are Ruby Wax, Bill Bryson and the Leader of the House of Commons, Penny Mordaunt. But support also came from more conventional quarters – the Wall Street Journal, New Scientist and The Times.

His fascination with science began, more than 60 years’ ago, when as a small boy, he observed a lizard on a rock in Camberley, Surrey, ‘I can remember it now. I must have been about three.’

It continued with How and Why Wonder books, which brought popular science to school children in the 1960s and 70s, with the help of which he began his own experiments at home as a boy. But his interest did not translate into school success. He enjoys telling the story, ‘I was in the remedial class, and I was bottom of that.’

Professor Foster adds:

‘The only thing I was any good at was swimming. I was an entirely non-academic child.’

He did like science, however, and was very keen on fossils and dinosaurs. Professor Foster admits, ‘I am still very interested in dinosaurs now.’

He bursts into laughter, ‘I was passionate about biology, but according to my headmaster, I was not very intelligent. He actually said that.’

So how did he go from there to being a professor at Oxford?

As though relating observations from an experiment, he adds in matter-of-fact terms, ‘What changed was in 1971 my father left [Russell was about 11]. Overnight, I grew up and I went from the bottom of the bottom class, to being at the top of the top class.’

Professor Russell Foster

Professor Russell Foster

It was to prove the first in a series of pivotal moments. An only child, the young Russell grew up in Aldershot with his mother, a nurse-turned children’s social care pioneer, and close to his adoring grandparents.

Why is sleep so important?

Do medical doctors understand sleep?

Do you sleep well?

Is the importance of sleep becoming recognised?

‘My mother looked after socially-deprived kids,’ he recalls. ‘She ran a local day home.’

His mother’s parents clearly had a major impact on the young boy, ‘My grandparents were remarkable people.

They were such kind people with immense generosity of spirit. They had German friends, although they had been bombed during the war.

They were utterly unprejudiced, very warm and very nurturing. So, even though my father left when I was young, it didn’t derail me, I was wrapped in a protective cocoon of love.’

‘I had just started at the local comprehensive when my father left. I hadn’t been at all academic and then I remember sitting in a class as they read out the names, in order of merit. I was wondering who came top of the class and it was me…

That’s a bit odd, I thought. I didn’t know what I was doing differently. But I went up through the classes. My mother had to pay for me to do O levels [CSEs were free] and I then went to Farnborough sixth form college…I loved it.’

And it clearly loved him, because more than 40 years later, when he was on Desert Island Discs, he mentioned his inspirational Biology teacher, Mrs Hodinott – who, along with his Geology teacher Miss Parker - got in touch with him after the programme.

‘It was fantastic,’ he beams. ‘We’re all getting together for Miss Parker’s 70th birthday.’

Professor Foster also recalls it was Mrs Hodinott who encouraged him to go to Bristol University, ‘Oxbridge just wasn’t on the radar in those days’.

‘It was the most exciting time of my life,’ he says. ‘I was meeting people who had the same excitement as I did. We stayed up half the night talking.’

University of Bristol

University of Bristol

He had been going to take Marine Biology (remember the swimming) but he switched to Zoology and Professor Foster’s life-long questioning interest in living processes began – questioning which led him directly to discoveries…

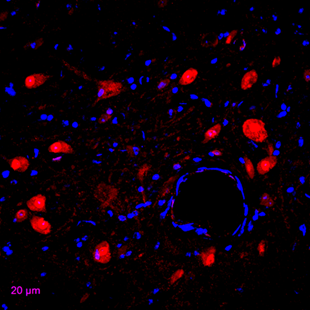

It was at Bristol University that Professor Foster, then a PhD student, began studying how birds detect day length and how this controls their seasonal behaviour like mating and migration.

'Unlike mammals, other vertebrates such as lampreys, frogs, lizards and birds have, in addition to their eyes, other light sensing organs such as the pineal, which are not involved in vision but are used to detect the changes in light intensity at dawn and dusk.

Back then we knew birds did not use their eyes for day length detection, but had little idea what they did use! In the end we were able to discover a light sensitive molecule buried in the hypothalamus of the brain’.

Bird hypothalamic photoreceptors

Bird hypothalamic photoreceptors

After Bristol, he went to the Netherlands and then Germany, to continue his investigation into non-eye photoreceptors, learning neuroanatomical techniques and the biochemistry of photoreceptors.

Another pivotal moment came when they had a visit from a US scientist, who was working in the same area – and who shared Professor Foster’s infectious enthusiasm.

‘I went to the University of Virginia for eight years. It was a formative time. Everyone was enthusiastic in the States. It was so different. There were no hierarchies. I’d never been to a lab meeting before – can you imagine that?’

University of Virginia

University of Virginia

While at the University of Virginia he began by working with a team studying the suprachiasmatic nucleus or SCN – a small region of the brain in the hypothalamus, directly above where the optic nerves from the left and right eye meet.

This work led to the discovery that the SCN was the “master” circadian clock regulating the daily rhythms of waking and sleeping.

But in parallel, he continued his photoreceptor studies, asking how the mammalian eye detects both light for vision and dawn/dusk.

This became the main focus of much of his later work back in the UK.

‘It was very, very difficult to come back from the USA,’ he says. ‘Our children were born there. But my wife’s career had been on hold (Elizabeth Downes, the successful lawyer).

There was a whole cohort of young people, such as me, who were excited by science and brought that back here.’

He adds, without much regret:

‘I halved my salary and came back – bringing my grant from the States with me. I moved to London – to Imperial.’

UK academic life was to be something of a rude awakening and another turning point soon came, when he applied for new grant support, only to be turned down.

‘I walked around Kensington Gardens, not knowing what to do. I felt that my career was in tatters. It was my birthday, so I went home and there was a surprise party for me…it was the last time I got very drunk.’

But, nothing daunted, the academic made up his mind to keep on kicking the door until they let him in.

He fired off applications for four or five grants to the then BBSRC, ‘I got two of them…they changed the rules because of me. You are now only allowed to apply for one grant at a time.’

Professor Foster’s work on how the mammalian eye regulates the circadian clock in the SCN then took off.

He showed that mutant mice lacking all their visual cells – the rods and cones – could still regulate their circadian rhythms normally.

But if the eyes were covered this ability was lost.

He says with undiluted excitement ‘there had to be another type of photoreceptor in the eye!’

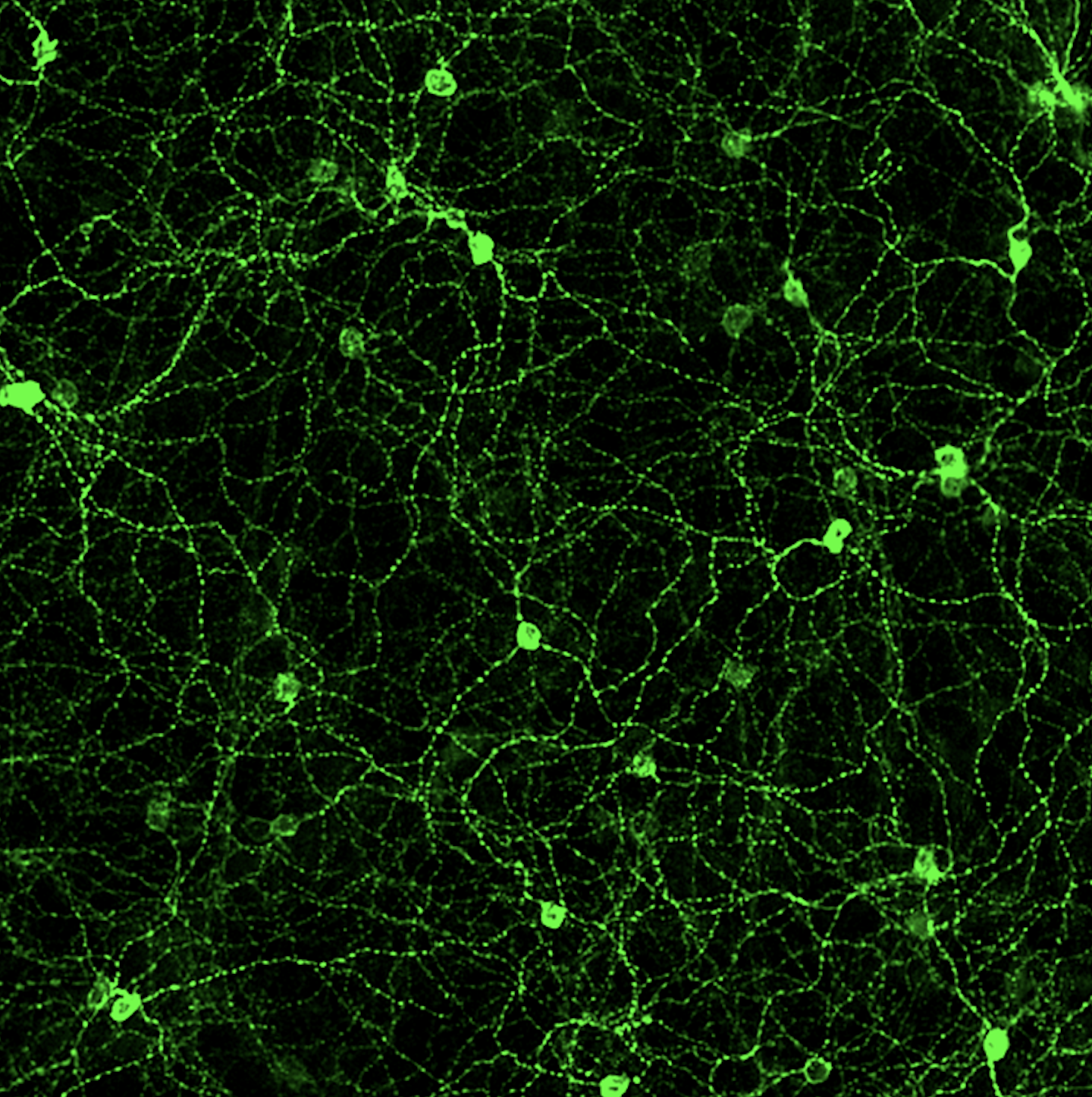

This led to the discovery by his team in the mouse that about 1 in 10 of the cells that form the optic nerve – the retinal ganglion cells – are directly light sensitive using a blue light sensitive photopigment.

Photosensitive retinal ganglion cells (pRGCs)

Photosensitive retinal ganglion cells (pRGCs)

‘The discovery of a 3rd class of photoreceptor, called photosensitive retinal ganglion cells, within the eye was completely unexpected and at first not believed by the vision community’ , Professor Foster explains.

And then he turned his attention to humans.

‘I was having a conversation about my work with a colleague who had been working with a severely blind patient who seemed to lack all their rod and cone photoreceptors, and I asked if she had any sleep problems, for example, was she waking at different times each day. The lady reported her sleep timing was regular’.

Professor Foster and his team then studied this individual in detail and discovered that we humans are just like mice and have photosensitive retinal ganglion cells or pRGCs.

Remarkably, these pRGCs also provide light information for many other tasks – even a subconscious awareness of light.

Professor Foster explains, ‘we asked her when a light was on or off,’ he says.

‘Even the patient said it was ridiculous – she couldn’t see any light at all – but when they gave it a try she guessed correctly every time. When we asked her how she knew, she said that she ‘just had a feeling’.’

He moved from Imperial to Oxford some 17 years ago. He recalls with considerable amusement the cold war-style meeting that led him up the M40, ‘JB [Professor John Bell, Regius Professor of Medicine] said we should meet.

‘I was on my way back from a meeting, and JB was going to a meeting, so, we met at Didcot station and chatted. He wanted me to come to Oxford.’

Professor Foster did not need persuasion.

‘Of course I knew Oxford was full of brilliant clinician scientists, and I was keen to work with them to translate our fundamental discoveries to improve human health and well-being.’

It was a combination of his own early experiences of struggling to get noticed and secure funding that have made Professor Foster particularly determined to open up science to early career scientists in his department, which he refers to as ‘succession planning for the next generation of researcher.’

Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin Building

Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin Building

‘Within the new Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin Building, we provide the opportunity on a daily basis for everyone in the building, from several different departments, to meet over a coffee and chat’

He says:

‘It’s important for researchers from different areas to discuss their work together for the cross-pollination of ideas. Many exciting innovations are coming from the interface between different disciplines’

His work has seen Professor Foster receive multiple awards and accolades – as a shelf in his office, crowded with unusual objects betrays.

The highly-decorated professor admits it seems ‘bizarre’ that a boy from the remedial class has been made a Fellow of the Royal Society.

And the eloquent and engaging academic appears genuinely delighted and even surprised at being asked to lead on public engagement.

Too much of his time, he says, is taken up with applying for grants. ‘It’s frustrating, but all part of the process. I still get grants turned down and it still hurts!’.

Professor Foster still has much to do in scientific terms and as his new Parliamentary role suggests. But he is already doing some succession planning – for when he does decide to step away. Although that seems a long way off.