A digital future for Oxford's gardens, libraries and museums

Oxford is a leading city for culture. It is home to some of the world’s most important collections of art, printed materials and specimens. These resources provide opportunities for academics and students to study diverse cultures, memories and heritage, as well as to consider contemporary questions about how we live. They are important for learning and teaching at the University, but also for the local community, schools and the wider public – who engage with them for learning, research or just pleasure.

Nearly 21 million items are held in the University’s six cultural and scientific institutions: the Bodleian Libraries, the Ashmolean Museum, the Pitt Rivers Museum, the History of Science Museum, the Museum of Natural History, and the Oxford Botanic Garden and Harcourt Arboretum. Further treasures can be found in the University’s Herbaria, and there are other, smaller collections of objects ranging from rare books to musical instruments.

The collections have grown over almost 900 years include items of historical significance and global interest, from the Magna Carta and the Alfred Jewel to J R R Tolkien’s archives. There are works of art, historical artefacts and everyday objects from around the globe, while the natural world is represented by millions of preserved specimens including now extinct animals, insects and plants, as well as some of the most diverse living plant collections in the world.

A digital world

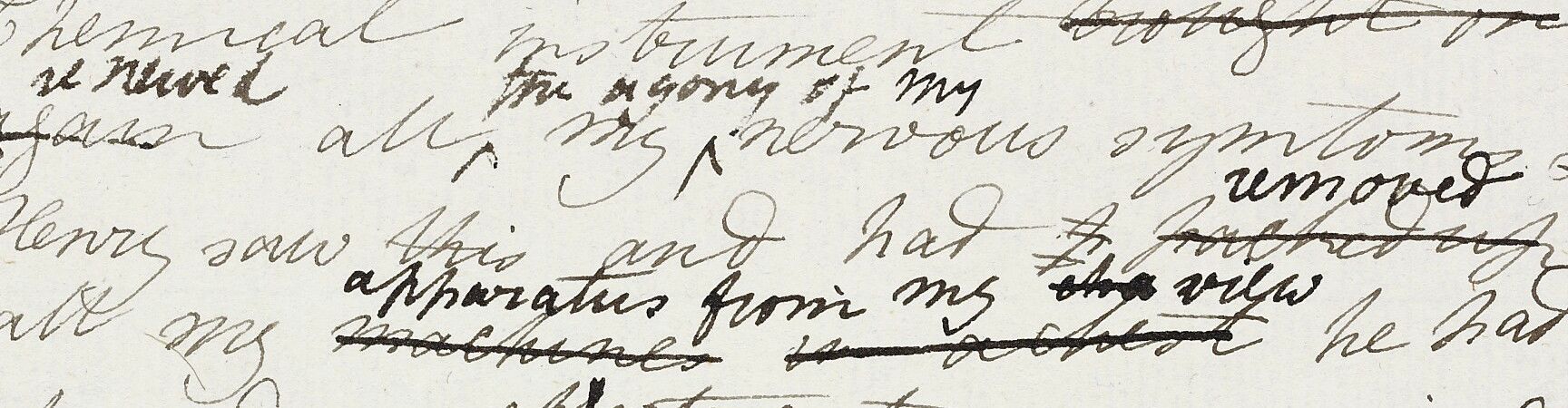

The collections are a resource for many millions of visitors – both in Oxford and, increasingly, online. Oxford has been a pioneer in embracing digital technologies, and it currently holds around 135 million digital images; the number of items with a digital surrogate has increased by nearly 5% over the past five years. These range from over a million high-quality images on the online image platform Digital.Bodleian to 3D objects on the University’s digital teaching platform, Cabinet. These digital resources are used by researchers, students and members of the public all over the world – a scholar in another country can zoom in to view detailed illustrations on a medieval manuscript, while students in local schools can explore 3D versions of a 19th-century Noh mask from Japan.

Digitising these resources, providing training, teaching and access to them, and considering how we manage data allows scholars, students and communities around the world to share in these collections – whether that means using them in the classroom, for research or for shared cultural connection.

This access can – and is – already transforming both the institutions and our communities. Research can now be completed at speeds previously unheard of, and items that were once difficult to examine inspire scientific breakthroughs. Classrooms now have access to resources that were previously limited to a few senior scholars, bringing education to life for students of all ages. New archives of data allow us to interrogate the systems that shape our daily lives.

These shifts enable world-changing research, helping us to solve problems in fields as diverse as healthcare and history. They transform teaching and learning. And they democratise our institutions, empowering our global peers to use the collections and allowing the preservation of information essential to a functioning society.

New ways of research

Digital collections, and digital ways of working with collections, are changing scholarly possibilities. AI technology is helping to restore and identify ancient Greek texts. Researchers are using digital tools to recreate the palace of Knossos. The Voltaire Foundation is publishing Voltaire’s complete works in a digital edition, enabling research to happen at a scale and speed that was impossible a decade ago.

Researchers are also able to collaborate with colleagues around the globe, and to work on previously disparate collections. Research on the Ashmolean Coin Collection is the product of this sort of global collaboration, as are efforts like the Polonsky German project, which brings together medieval German manuscripts into a virtual scriptorium.

This type of research unlocks new understandings of our history, but also leads to new scientific discoveries. Digital collections like Oxford’s Herbaria, a collection of plant specimens dating back 400 years, and the Natural History Museum’s British Insect Collection are critical tools in understanding the natural world and changes to it. In the face of climate change, plummeting biodiversity and habitat loss, these collections have much to contribute when it comes to confronting today’s environmental threats.

Enriching learning and teaching

A classroom in Cornwall engaging with insects in the Oxford Museum of Natural History. Physics researchers coming together with the University’s History of Science Museum and the Bodleian to reach students across Oxfordshire. Ashmolean treasures you can import into Animal Crossing. Undergraduate students using augmented reality to study items from cultures from around the world. Digital collections, and digital methods of outreach, mean these are now standard practice in Oxford.

Oxford’s collections have been used to engage people from all age groups. The museums and libraries work closely with local schools to provide access to collections, but have also developed both lesson plans and live remote sessions for those further afield. Digital scholars find new ways of bringing texts to life with AI-powered Shakespearean chatbots. Within the University, students can use digital collections to explore objects and texts up close, providing them with opportunities to see objects that may have been off limits or behind glass before.

Global communities

During the pandemic, people around the world shifted online to work, learn and find entertainment. Oxford’s museums and libraries had already embraced the digital world, but their efforts to provide deeper engagement accelerated. The Pitt Rivers Museum, for example, used specialist digital microscopes and cameras to show textiles from Nagaland, Palestine, and the northwest coast of America to weavers from those communities and enrich the textile collections’ information.

Similar projects to engage with communities around the world are now a part of Oxford’s regular practice. The Ashmolean’s #IsolationCreations inspired 3,000 people around the world to respond to the museum’s online collections with sketches, poems and photos of their own, from Egyptian figurines in Blu Tack to the Alfred Jewel photoshopped onto flatbread. The Bodleian Libraries make religious texts like the Shikshapatri available for worship to those who cannot visit it in person. Other projects bring digital versions to those who haven’t ever accessed digital collections before; the Precious and Rare: Islamic Metalwork exhibition brought a ‘digital twin’ version with objects from the University’s History of Science Museum to entirely new audiences. Oxford’s collections are equally enriched by these exchanges.

The Pitt Rivers Museum Talking Threads project used specialist digital microscopes and digital SLRs to show the textiles meaningfully and in detail to weavers and other interested community members remotely

The Pitt Rivers Museum Talking Threads project used specialist digital microscopes and digital SLRs to show the textiles meaningfully and in detail to weavers and other interested community members remotely

The digital century

Not all the collections in Oxford must be digitised; increasingly, our libraries and museums are acquiring ‘born digital’ collections – from the email and computer archives of politicians like Barbara Castle to the UK Web Archive. As a growing percentage of the world’s information is generated in digital formats only – 197.6 million emails were sent each minute in 2021 – the ability to save these new types of material is crucial.

The Bodleian Libraries’ work in this area is world leading, and it’s not as simple as storing emails on a hard drive. This complex area requires significant infrastructure and expertise as we explore new forms of data. It also puts libraries at the heart of some of society’s most pressing questions – who gets to control our data, and how is it used? The Bodleian aims not only to manage increasing numbers of hybrid archives, but also to consider web, algorithm and social media preservation and its role in a democratic society.

'There is still time for libraries and archives to take control of these digital bodies of knowledge in the early twenty-first century, to preserve this knowledge from attack, and in so doing, to protect society itself.'

Richard Ovenden, Bodley's Librarian, in Burning the Books

Technological leaps

Digitising collections is more than just point-and-shoot photography. Even at its most basic, it requires skilled teams to photograph or scan precious and fragile materials, ensure that the information – or metadata – about each item is complete, and manage the digital infrastructure required to make these digital collections available.

Oxford is world leading in more than just its objects, however; it is paving the way for new standards in digital collections. It was there in the early days of the International Image Interoperability Framework (IIIF), a set of open criteria for delivering digital objects online. More recently, the University has worked on new ways to present 3D objects alongside the contextual information that is so important for learning and teaching, and to use augmented and virtual reality to make these items available to students, visitors and members of the communities from which the objects originated. The Oxford Museum of Natural History’s First Animals exhibition created a digital reconstruction of the ocean floor 518 million years ago, based on digitised fossilised remains, to show how creatures looked and moved.

The University is also trying new ways of scanning and imaging items. The Bodleian has used ‘space-age’ hyperspectral imaging to reveal what lies beneath the surface of early Aztec codices from Mexico – ancient manuscripts in book form. 3D scanning of the Gough Map, one of the earliest maps of Britain, has revealed previously unseen elements of its construction. Other techniques are born out of necessity; the Botanic Gardens are working creatively to ‘digitise’ living plants, whose shapes require creative approaches. The Pitt Rivers Museum has been using CT scans and 3D printing to provide accurate replicas of musical instruments from the Bate Collection so that members of originating communities, researchers and students can play them to discover the sounds they make, without damaging the originals.

The future

Oxford aims to create a digital, data-rich experience, supporting global learning and culture by ensuring that the cultural and scientific heritage of the present and future, in digital form, can be preserved and used by generations to come.

It plans to implement a mass digitisation programme, on a level unprecedented at any other university. The project will capture not only the images themselves, but the associated curatorial and community knowledge that is so valuable. Uniting the collections culturally and scientifically will revolutionise their accessibility, creating a platform for global learning, teaching and research. Transcending geographic, cultural and economic boundaries, it will provide an incredible opportunity to engage the broadest possible public with Oxford’s knowledge, past and present.