Digitising the natural world

Digitising our natural science collections provides opportunities for understanding our world and its future.

Oxford is home to some of the greatest natural science collections in the world, from 5 million insects and half a million fossils at the Museum of Natural History to more than a million dried, pressed plants, flowers and fruits in the Oxford University Herbaria. Digitising these collections provides opportunities for understanding our world and its future.

These collections are a unique prism through which we can understand how the earth and its natural systems have formed, the role of biodiversity, and the impact of human activity and environmental change over thousands of years. They are helping to answer questions vitally important to a rapidly expanding global population, such as food security, biodiversity loss and combat climate change. Digitising the collections will enable scientists locally and globally to study, share their knowledge and collaborate on future research.

The Herbaria

The University’s Herbaria is founded on the herbarium of Jacob Bobart the Elder, a German botanist who became the first head gardener of the Oxford Botanic Garden in 1641, and the oldest samples in the collection date from 1595

Over the centuries, thousands of plant collectors have contributed to the collection, including Charles Darwin.

Much of the older collection is bound in books, while later samples are mounted on card with accompanying details of when, where and who collected them. Among the slides, blocks, original manuscripts and hand-painted illustrations are approximately 40,000 irreplaceable ‘type specimens’. Type specimens are reference samples when a plant is first given its scientific name and are critical to the understanding of plant diversity and evolution.

Many plants found in the herbarium are endangered, or now extinct in their original habitats because of over-collection, disease or the introduction of invasive species into the local ecosystem.

An 1848 sample of Vetch from the Azores, for example, is the only known example of the plant, after a landslide destroyed the only known population in the wild.

Some species in the collection, such as the Lady Slipper Orchid, are now more common in the herbaria than they are in the wild, reflecting the damage done by over-enthusiastic plant collectors in the past.

The records provide an important tool for scientists looking into species conservation through the prism of biodiversity and the challenges of environmental change and food security. The samples give significant insights into the environmental conditions of the past and show how plants have changed genetically over hundreds of years.

Museum of Natural History

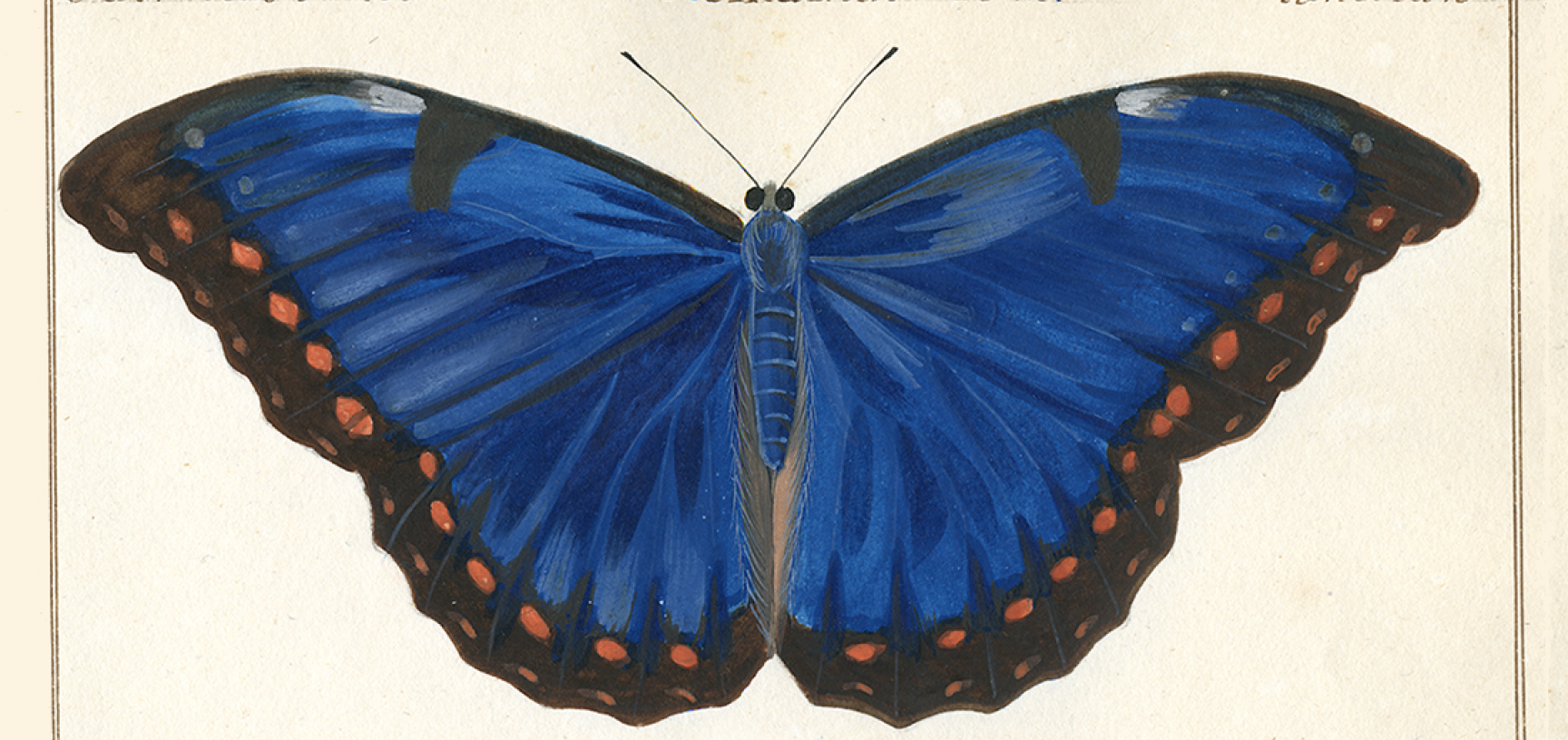

Oxford’s Museum of Natural History holds over 7 million historical and modern specimens. This includes five million insects; over half a million fossils, rocks and minerals; zoological specimens; and a substantial library and archive.

The museum was established in 1860 to draw together scientific studies from across the University, although its collections date back much further. The museum holds over 30,000 zoological type specimens and a number of world-famous items, such as the world's first scientifically described dinosaur – Megalosaurus bucklandii – and the only soft tissue remains of the now extinct dodo.

These collections are a key asset for researchers around the world. The Museum's British Insect Collection, for instance, provides extensive information for researchers on the biodiversity of Britain, documenting how it has changed since the eighteenth century, through the Industrial Revolution to today’s post-industrial landscapes. Other collections include one of the world’s most important collections of Middle Jurassic dinosaurs and the oldest fossil mammals.

A 3D scan of the Megalosaurus bucklandii jaw bone

Digitisation: challenges and benefits

Recognising both the fragility and importance of collections like this, the Museum and Herbaria have begun to digitise their collections, to ensure their survival for future generations as well as opening up the collections to a wider audience.

The Oxford University Herbaria plays an important role in ecological, taxonomic and conservation research in the UK and abroad. The process of digitising the collection started in 2019, and around a third of the total collection has been digitised so far. The Herbaria database includes images and metadata, such as transcriptions of the hand-written notes accompanying the samples, who collected the sample, where and when. The catalogue is dynamic, with additional information, such as genetic analysis of the specimens, being added as new research becomes available.

The Museum of Natural History has over 500,000 items online, ranging from palaeontology to insects and archives. Specific projects aim to address particular needs and priorities. The archive of William Smith, for example, has facilitated the study of early mapping techniques and the history of 19th century geology in England.

At the other end of the spectrum, researchers in the museum are applying state-of-the-art computational methods in palaeontology, analysing specimens digitally and in 3D. The MorphoSource project provides an online repository for this 3D data, representing the world's natural history, cultural heritage, and scientific collections. These are helping researchers, students and educators around the world learn more about extinct creatures as well as those more recent.

Many of the specimens are fragile or brittle, making them difficult to handle, and without continual care are prone to damage. Creating digital versions will preserve these unique resources for future generations and make the specimens readily available to researchers and students worldwide.

Making collections available digitally also reduces the need for international travel to study these delicate and valuable resources.

Digitising an intricate and delicate resource comes with a very specific set of challenges, such as the huge volume of information to be converted to digital form. The process of digitising historically important collections may be difficult, but it is a worthwhile investment that significantly improves research infrastructure in Oxford, the UK and globally. The value of research enabled by the digitisation of these natural history collections is limitless, furthering research in biodiversity, conservation, the history of science, medicines and agricultural research.