SCG-Oxford Partnership

By working with the University of Oxford, SCG is placing sustainable innovation at the heart of its business strategy

As a global producer of cement, packaging and chemicals, Thai business group SCG knows that it must take bold steps to reduce its impact on the environment.

By placing sustainability at the heart of its innovation strategy, SCG plans to embrace the circular economy, boost recycling rates and lower greenhouse gas emissions.

More than a decade ago, Cholanat Yanaranop, then President of SCG Chemicals (SCGC), realised the business needed to form a lasting research partnership with leading academics to help the company accelerate innovation and make its operations more environmentally friendly.

It was a tough challenge to find the right fit, until one of the company’s employees, studying at the University of Oxford for a DPhil, suggested that research by Professor Dermot O’Hare in the Department of Chemistry could help solve some of the company’s sustainable innovation challenges.

Early conversations around working with nanomaterials and novel catalysts went so well that the foundations of a partnership were formalised in 2012 by forming the SCG-Oxford Centre of Excellence (CoE) within the Department of Chemistry.

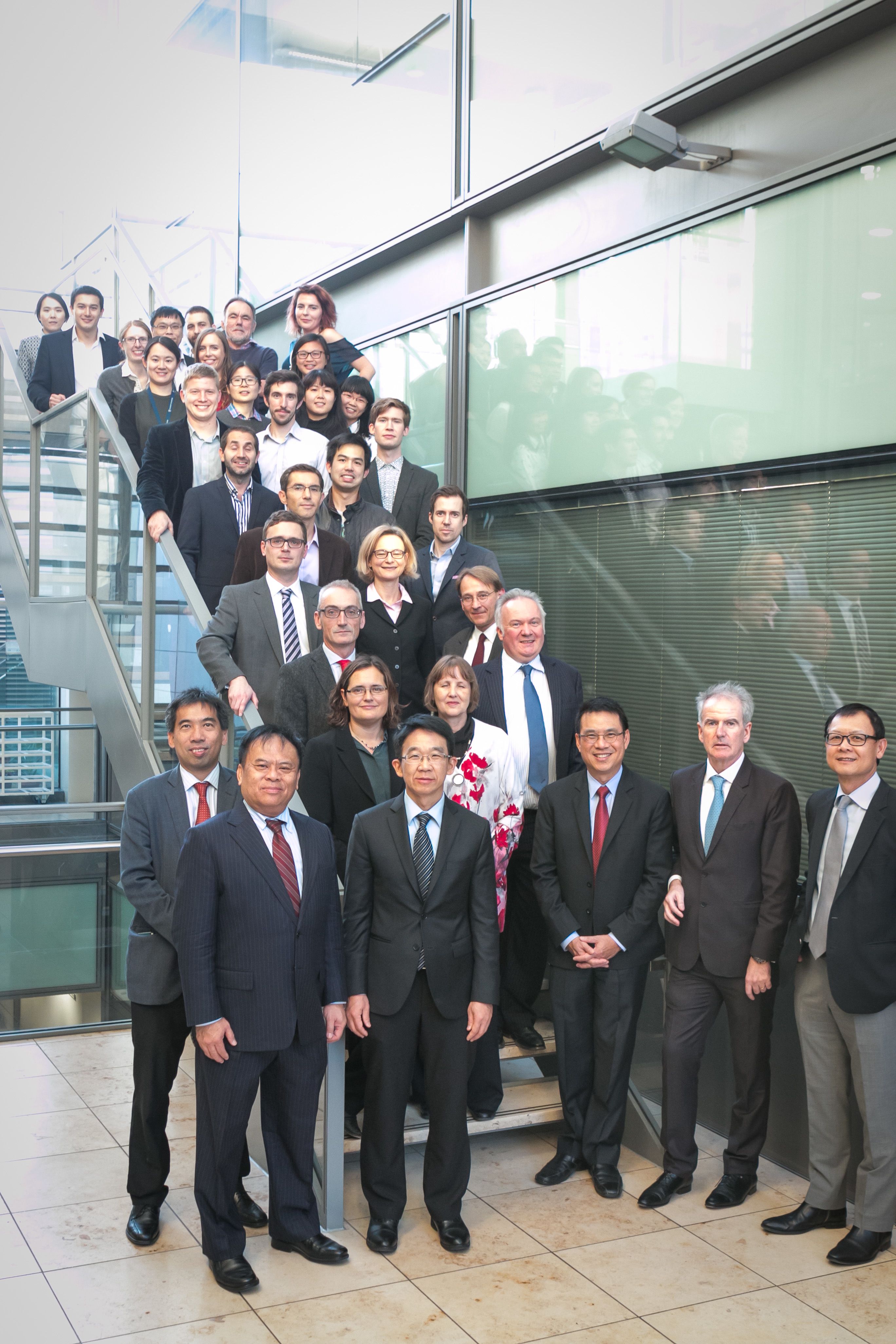

Partnership colleagues at the CoE opening in 2012

Partnership colleagues at the CoE opening in 2012

A little over a decade later it remains SCG’s prime academic collaboration, prompting the company to open its own research facilities in Oxford, at the University’s Begbroke Science Park. Cholanat Yanaranop reveals the partnership is successful because there is an agreed separation of roles.

'We formed the Centre of Excellence so we could work together on a partnership where the University is responsible for invention, and we take charge of innovation,' he explains.

'There’s no way we could make new discoveries like the University of Oxford does. It has the best chemistry labs and equipment and the most talented team of scientists. SCG takes the scientific discovery through all the downstream processes it has to go through in industry. We make it scalable, sellable and useful to people in our markets. Having these two sets of responsibilities enables us to avoid crossover and delays, so we can truly innovate at pace.'

SENFI opened in 2019 at Begbroke Science Park

SENFI opened in 2019 at Begbroke Science Park

Packaging recycling breakthrough

One of the most notable advances from the partnership is already poised to play a pivotal role in boosting food packaging recycling rates. While most of today’s plastic food wrapping, such as crisp packets, can be recycled, in reality it is often consigned to landfill. The thin metallic layer on the inside of the packet is good at keeping food fresh, but it can be expensive to strip away from the plastic layers between which it is sandwiched.

As Professor O’Hare explains, the challenge to replace the metallic layer was posed to his team and, although he did not have an immediate answer, the time that SCG put into his research has now paid off.

'SCG funded and supported the project for quite a long time. It’s one of the things I really appreciate about SCG, they fund long-term horizon activity.'

'We have produced a coated layer in our lab that creates a higher barrier to oxygen than metallized film. It works as a tiled wall of tiny little bricks. It’s non-toxic, inorganic based, and made in water. This presented a challenge to get it on to a plastic film but SCG allowed us to put in the time to do it. I think it’s one of the nicest pieces of work that we've done through SCG support.'

The new material is being used already in snack packaging in Thailand and SCG hopes it will soon be picked up by customers beyond Asia.

'I place the Oxford Centre of Excellence as an important part of our innovation team. The Centre plays a role in discovering new materials that everyone can sustainably use in daily life applications. We are now expanding to work with other departments and young academics to strengthen our network and gain insight into exciting new technologies.'

Suracha Udomsak Photo credit: SCG

Suracha Udomsak Photo credit: SCG

Circular approach to cement

Boosting recyclability of packaging is core to the partnership, as it creates circular processes in manufacturing its products. By being able to reuse or repurpose ingredients or components, the company aims to use fewer resources and reduce pollution.

It is here that Professor O’Hare’s team is striving to fix a pressing problem for SCG in both its polymer and cement-making divisions. Responsible companies in the industry realise they must tackle the high emissions linked to what is one of the most energy intensive processes of heating rocks to form clinker and then cement.

Part of the solution could come from the Oxford team’s work on capturing carbon dioxide from cement-making and converting it into a feedstock for producing plastic.

'Everyone wants to reduce CO2 emissions, and direct capture from a flue inside a manufacturing process is likely to be more effective than trying to take it out of the air because it’s more concentrated,' he explains.

'Our aim is to capture the CO2 from the cement business to prevent it being released into the atmosphere and then use it as a feedstock to make plastics, instead of oil.'

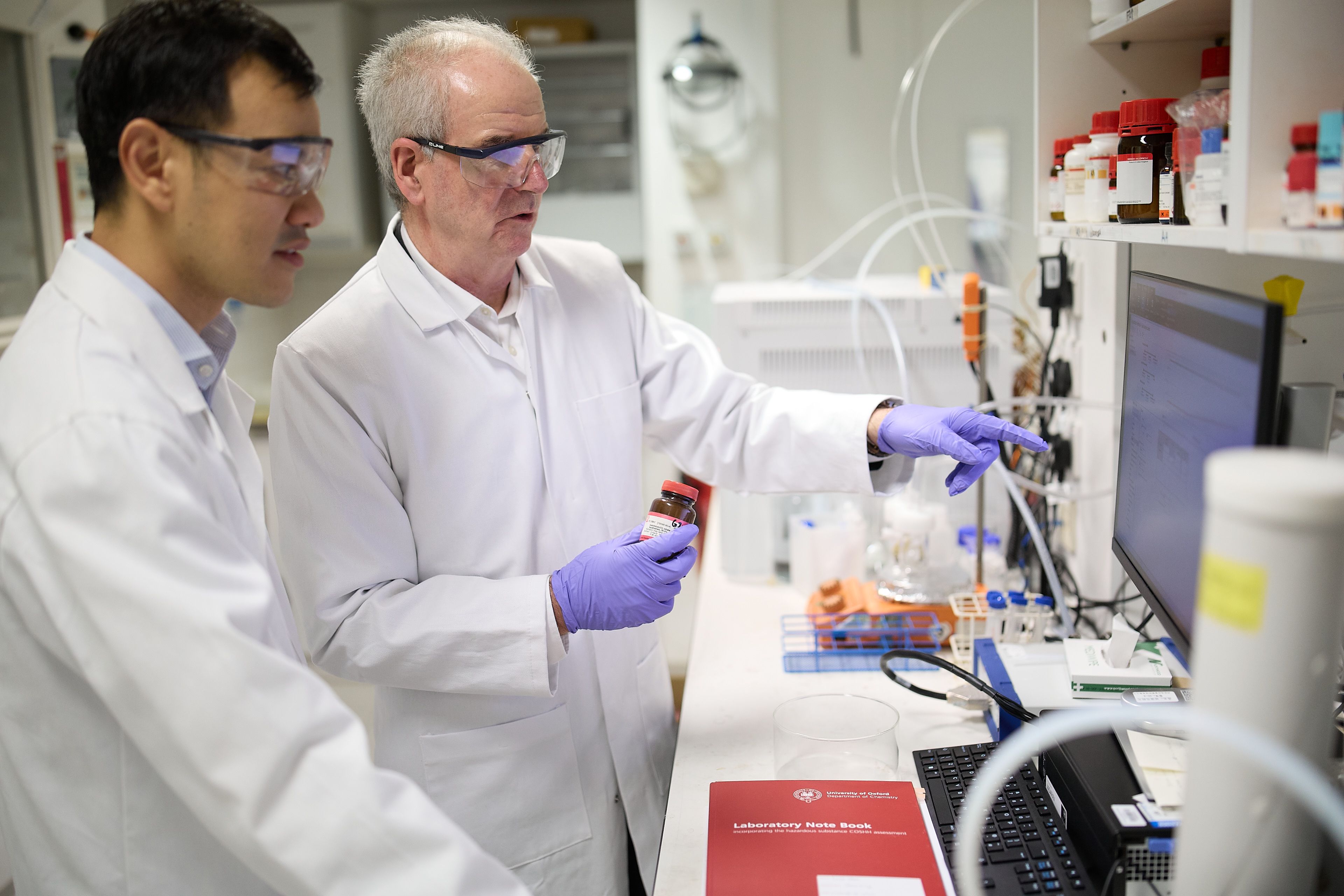

Professor Dermot O'Hare

Professor Dermot O'Hare

It’s a noble aim, with a very real challenge because CO2 is such an inert and stable gas. Professor O’Hare is channelling new thinking to the problem.

'Using hydrogen you could turn CO2 into water and methane,' he adds. 'We obviously don’t want to release methane because that’s a lot worse greenhouse gas than CO2, instead we want to turn it into methanol, from which we believe we can create the building blocks to make plastics.'

Due to the high cost of hydrogen, the team is trying to make the gas in a renewable way through electrolysis using renewable electricity, passing an electrical current through water. If successful, it could enable SCG to take a waste pollutant from one part of its operations, cement making, to replace the oil used in its plastic production, as a more environmentally friendly feedstock.

Empowering postgraduate innovation

The partnership offers multiple postgraduate research opportunities, attracting the brightest talent to the Centre of Excellence, people who want to push the boundaries of chemistry, as well as helping industry reduce its environmental impact.

While some of the challenges posed to the group come from SCG, many of the discoveries assume what Professor O’Hare refers to as a 'bottom up approach' where a discovery from the team is presented to SCG. They may not have asked for a specific outcome but when a breakthrough is discovered, they have the first opportunity to fund further research and commercialise it.

A case in point comes from the research of Dr Clement Collins Rice, who studied sustainable and efficient production of more durable plastics for his doctorate, as part of the SCG and University of Oxford partnership. His work is now ready for SCG to decide if they think it has a viable commercial application.

'I did my master's with Professor O’Hare and wanted to stay and work with the team on trying to find a way to make very strong polymers more efficiently,' he says.

Dr Clement Collins Rice

Dr Clement Collins Rice

'As researchers we get the best of both worlds. We work on discovering new chemistry in the lab which could be put to good use in industry. We’ve found what we believe to be a better, more sustainable catalyst to make these plastics that are tough enough to be used in a wide range of applications from bulletproof fabrics to lightweight joint replacements which are accepted more readily by the body’s immune system than metals. The great part about the partnership is that we can now take this to SCG to see if they would like to take it forward.'

The dedication to placing sustainable innovation at the heart of the partnership has been helpful in attracting the highest quality researchers, not just from the University of Oxford but also other institutions.

DPhil student, Rebecca Jones, joined the team after completing her master's at Imperial College London because the partnership allowed her to combine two passions – scientific discovery and sustainability. She is working on creating polymers from renewable, natural resources in the most environmentally friendly way possible.

'The partnership is focussed on sustainability and that is hugely important to me. I’m working on making plastic from corn-based starting materials but not using a conventional catalyst, such as tin, but rather a catalyst, containing magnesium or calcium, which is more abundant and less toxic. It’s wonderful to have the opportunity to be working on new discoveries that can benefit the environment.'

In addition to working on sustainability, a key aspect of working with the group, for Rebecca, has been the support at the University for women in STEM. She has attended several meetings which support staff and researchers, and provide entrepreneurial advice.

This support empowers researchers to make new discoveries and then spin them out into companies. This is DPhil student Katherine Laney’s aim. She has already received a Jamie Ferguson Chemistry Innovation Award to turn her work on layered hydroxides into a business that will look at ways of improving the performance of renewable energy sources.

'I was attracted to the University of Oxford and working with Professor O’Hare’s team with SCG because the focus is on solving real world problems,' she says.

'There’s such a good network here, supporting people to take their ideas forward. It’s a really steep learning curve but Oxford University Innovation (OUI) has been incredibly helpful in supporting me to protect my ideas. I’ve been working on patenting and building the right team to commercialise it.'

While much of the work achieved through the partnership involves complex chemistry which might not be immediately visible to the public, the recyclable food and snack packaging breakthrough could soon be in the hands of consumers across the world. Hopefully, that will mean that consumers can put a crisp packet in the recycling bin with the assurance that it really will be recycled.

100 publications

CoE projects have resulted in nearly 100 publications in international peer-reviewed journals

2012

The year CoE was established and since then has been associated with over 20 Chemistry Professors, 30 Postdoctoral Research Fellows and many PhD students

50 projects

have been funded, amounting to over £20 million

2019

The CoE won the prestigious Industry-Academia Collaboration Award from the Royal Society of Chemistry